KIKUCHI Taihei

(Doctoral Program, Studies in Language and Society, Graduate School of Language and Culture, Osaka University)

The situation surrounding the Shan language in Myanmar

The Shan language, which is related to the Thai language, is spoken mainly in the Shan State of Myanmar and northeastern Thailand. Compared to the number of native speakers of the Shan language, estimated to be about 3.3 million, the volume of publications in Shan are not so large. This reflects the social situation surrounding the language itself.

In Myanmar, Burmese, the national language, is used in public education. Even in Shan State schools, it is necessary to speak in Burmese because Burmese-speaking teachers are sent there. In addition, university entrance examinations (high school graduation exams) known as the “Sedan” are only available in Burmese. As such, it is essential to master Burmese to access to higher education in Myanmar. Those who seek further education and employment opportunities often go to Thailand and other foreign countries. Therefore, Shan youth prioritize learning Burmese and English much more than the Shan language. Due to this there are cases where they are native speakers, but have poor literacy skills in Shan scripts.

As a result of this situation, publishing in the Shan language and educating the public through these publications is an important activity for indigenous Shan to pass on their identity to the next generation. One of the largest organizations in Shan State dedicated to educating young people is the Kaw Dai Organization (KDO) founded in 1998 by Sai Phong Kong and Sai Hseng Pha who were migrant workers in Bangkok at the time. At present, the organization has around 400 staff and members [1]. (Previously, all those involved were called KD staff, but the organization was reorganized in FY2022 and consists of staff and supporting members).

KDO currently runs three schools in Karli, Hsipaw, Laihka, and small branches in other villages. The schools run by the organization enrol children from 6 to 17 years old and teach them Shan language, Shan history, English, geography, mathematics, science, biology, and Burmese (primary and secondary level). After graduation students can go on to a community college, which is also run by KDO, to obtain a diploma degree after three years of study. However, students must take a separate high school equivalency exam to enter other general universities, as the school is not accredited by the government. A woman, who works in the organization, explained the importance of education and her motivation for the activities even though the pay is not high, stating “I want children to learn about Shan culture, Shan literature, Shan language, and the real Shan history, and to speak English as well.”

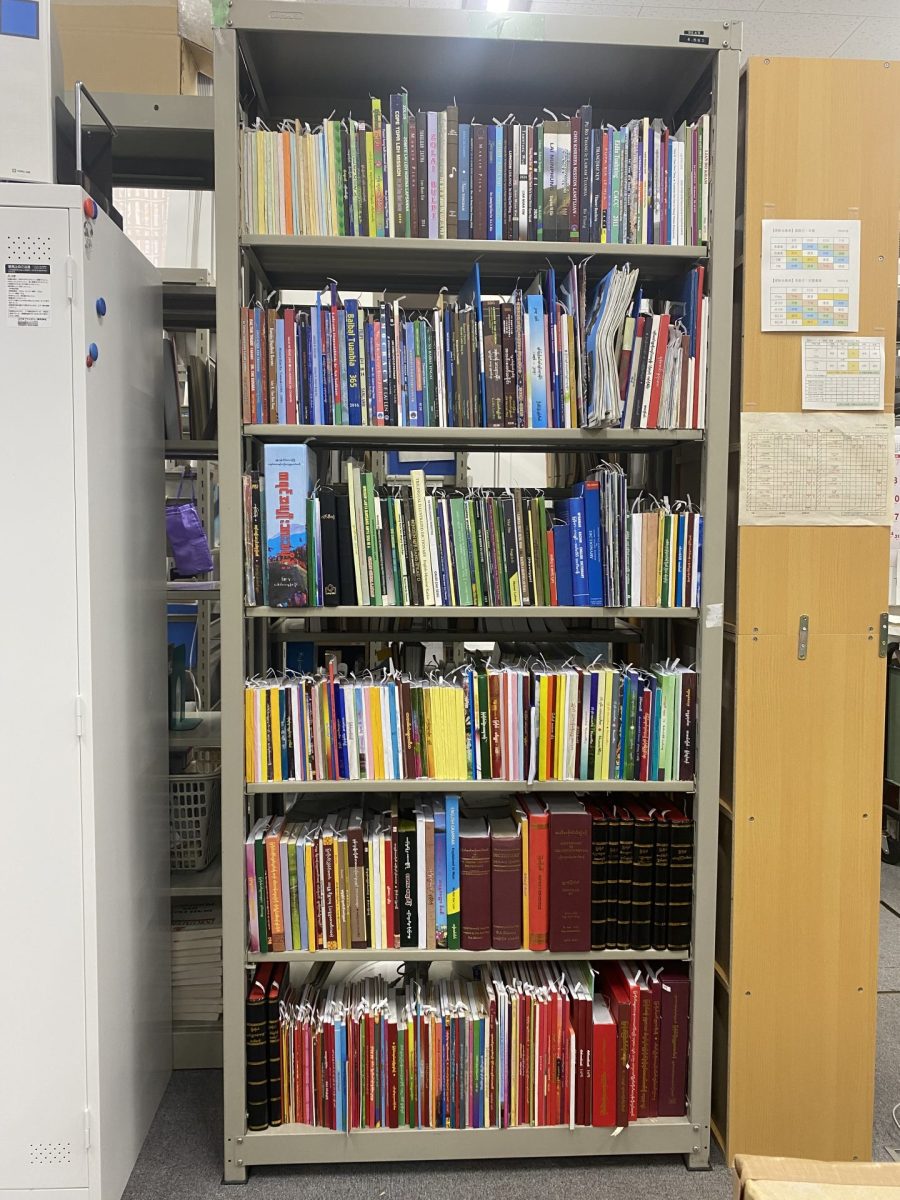

The collection of Shan publications by IPCR

In the effort to preserve ethnic minority identity, a key concept is language. When, where, and by whom are publications in minority languages, which form the basis of such activities, carried out? Under a joint research project titled “Collecting and Analyzing Materials Published by Local Communities and Ethnic Minorities in Myanmar: Considering Grassroots Pluralism” (PI: Michihiro Wada, associate professor of the Kanda University of International Studies FY2020−2021) funded by the “International Program of Collaborative Research (IPCR),” Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, we imported books in minority languages in Myanmar, especially Mon, Chin and Shan in order to explore the publishing situation within the country.

The total we gathered was 620, all of which are housed in the CSEAS library, Kyoto University and of these, 49 were written in Shan. The bibliographies of these items were prepared by the author in cooperation with the library and registered in the bibliographic database system, NACSIS-CAT. In January 2022, an additional 231 books were purchased through a local bookseller in the Shan State via Bangkok. The bibliographic data of these books are still in preparation but will be registered in NACSIS-CAT via the CSEAS library.

Shan materials collected this time by genre are 2 in language, 28 in literature, 2 in philosophy, religion, and art, 2 in history and geography, and 15 in society, culture, psychology, and education. The majority of these are literary works such as fiction and poetry and works on Shan culture and society. The largest number of publications came from Taunggyi, the capital of Shan State, with 12, followed by Yangon, the largest city in Myanmar, with 9. This trend can also be seen in other materials. It seems that publishing centers are generally in urban areas. The largest number of works by the same author was by the well-known writer Loog Tan Kay (1924−2017).

The expansion of a Shan fairy tale: “Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim”

Below we introduce a famous Shan fairy tale titled “Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim” which is included in the books we have collected. This story is said to have been created around the 1870s by a 19th century female writer, Nang Kham Ku (1853−1919), based on a true story. Nang Kham Ku was the daughter of Sao Kang Hso (1787−1881), a renowned Shan monk and scholar and one of the writers listed as the “Nine Great Writers” of Shan literature.

“Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim” is a tragic love story. Khun Sam Law, a young man from Kengtawng in eastern Mong Nai, the Shan State, falls in love with Nang Oo Peim, the daughter of a wealthy family, while on a business trip and soon after they get married. But after some time away from his hometown, Khun Sam Law leaves behind his pregnant wife and returns home temporarily. At first his intention was to return home for a short stay, but his mother, who did not approve of his marriage, makes it difficult for him to leave. Worried about her husband’s late return, Nang Oo Peim follows him to live with her mother-in-law.

Nang Oo Peim is a very beautiful woman, but not adept at housework. As a result, she is constantly harassed by her mother-in-law who treats her badly. Nang Oo Pein can no longer stand her and finally tries to return to her parents. Unfortunately, she gives birth to a stillborn child on the way (the dead child is placed on a tree and eventually reborn as a bird). Nang Oo Peim herself makes it back to her parents but dies of an illness she contracted on the way home. When Khun Sam Law learns of this, he is deeply saddened and takes his life. However, his mother, who never likes their relationship, separates their bodies, which lie side by side with a partition. It is said that Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim are finally reincarnated as stars and live together [2].

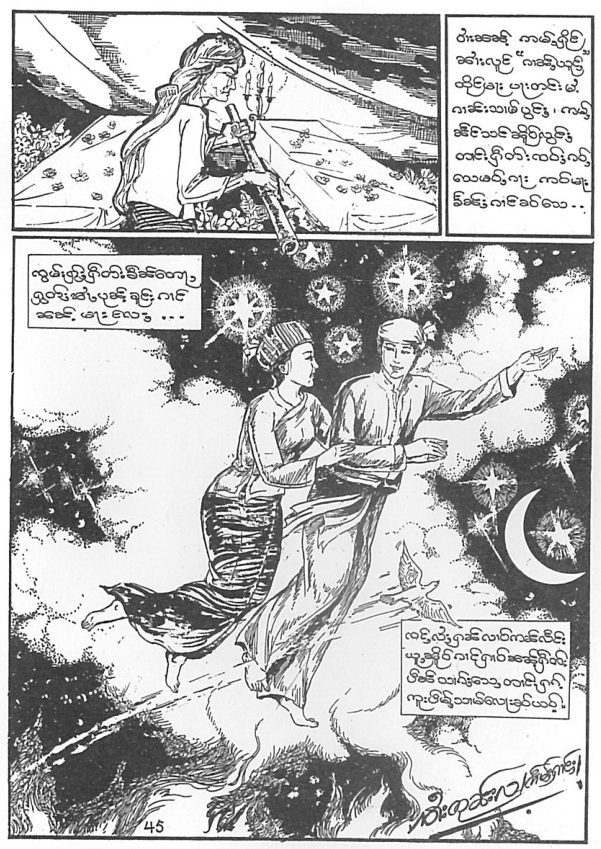

One of the collected materials dealing with “Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peng” is a cartoon edited by Loog Tan Kay [3] (published in 1999, 45 pages, with black and white illustrations, 19cm). Loog Tan Kay was from Namhkam in Shan State. Although he had no higher education, he produced an extraordinary number of publications and was a scholar who, in 1940, was asked to develop the new Shan script and write textbooks.

The other is “34 Shan Folklores,” a collection of Shan fairy tales for children [4]. This book is a compilation and reprint of two Shan texts published by the Shan State Government Education Department, based in Taunggyi, in 1939 and 1940 during the British period (published in 2019, 200 pages, with black and white illustrations, 24 cm). The story of “Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim” is included in No. 25 of this collection.

“Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim” has been told repeatedly by the Shan people in various forms, including novels, plays, poetry, and songs. Recently, numerous songs and storytelling movies about the story have been posted and viewed on Facebook and YouTube. Indeed, Sai Jerng Harn, the former popstar, and Sao Hsintham, a Buddhist monk started the controversial “Shan Movement” in 2014 in Kengtawng. Based on this story, Sai Jerng Harn claimed to be the incarnation of Khun Sam Law while the Shan Sangha blamed him for damaging the purity of Buddhism. Unrelated to this movement, Shan immigrants in Chiang Mai, Thailand now use the story to place themselves in the lineage of Khun Sam Law at every Shan Valentine’s Day celebration [5]. Shan publications must be important sources to know about Shan representations, their ethnic consciousness and the current situation surrounding Shan language.

Sources written in the Shan language are rarely collected and preserved systematically. Preserving and making them available to the public will contribute not only to Shan (Tai/Tay:) Cultural Area studies in Japan, but also to Shan people all over the world by presenting their publication system through the bibliographic information in CiNii Books [6].

Notes

[1] https://www.kawdai.org/about-us (Last accessed on June 25, 2023).

[2] Readers who want to learn more about “Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim” in English can find the digital book, “The Orion Stars: Tai Mythology of ‘Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim’” by Sao Noan Oo (Nel Adams). https://www.scribd.com/document/52835804/khun-Sam-Law-Nang-Oo-Peim (Last accessed on June 25, 2023).

[3] လုင်းတၢင်းၵႄး၊ 1999၊ ၶုၼ်သၢမ်လေႃး ၼၢင်းဢူးပဵမ်ႇ [Khun Sam Law and Nang Oo Peim] ၊ တႃႈၵုင်ႈ: မွၵ်ႇၵူႇသွႆႈၸႅင်

[4] ၸုမ်းသူင်ပပ်ႉတႆး (Shan Book Club)၊ 2019၊ ဢပုမ်ႇၵဝ်ႇတႆး ၃၄ႁူဝ် [34 Shan Folklores] ၊ တႃႈၵုင်ႈ: မွၵ်ႇၵူႇသွႆႈလႅင်

[5] Phorn Khamindra. 2016. “Affirmation of Shan Identities through Reincarnation and Lineage of the Classical Shan Romantic Legend ‘Khun Sam Law.’” Thammasat Review. 18(1): 1–26.

[6] https://ci.nii.ac.jp/books/?l=en (Last accessed on June 25, 2023)

This article is also available in Japanese. »

〈図書室コレクション紹介〉菊池泰平「出版物から読み解くシャンの表象」