Chika Yamada (Public Health, Area Studies)

The process by which foreign technology is transmitted and diffused to a particular region is truly complex. In my research on how a particular public health technology spreads in Indonesia, I find myself constantly grappling with how to interpret this process. A breakthrough came with Jiat-Hwee Chang’s A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Colonial Networks, Nature and Technoscience (2016), which I picked up on the recommendation of Professor Lawrence Chua. Although I initially approached this book for a different project, and it focuses on the history of architecture in tropical regions (primarily Singapore), it unexpectedly provided valuable insights into public health in Indonesia. This serendipitous discovery echoes Professor Yoko Hayami’s account of the thrill of finding relevant connections in seemingly unrelated fields.

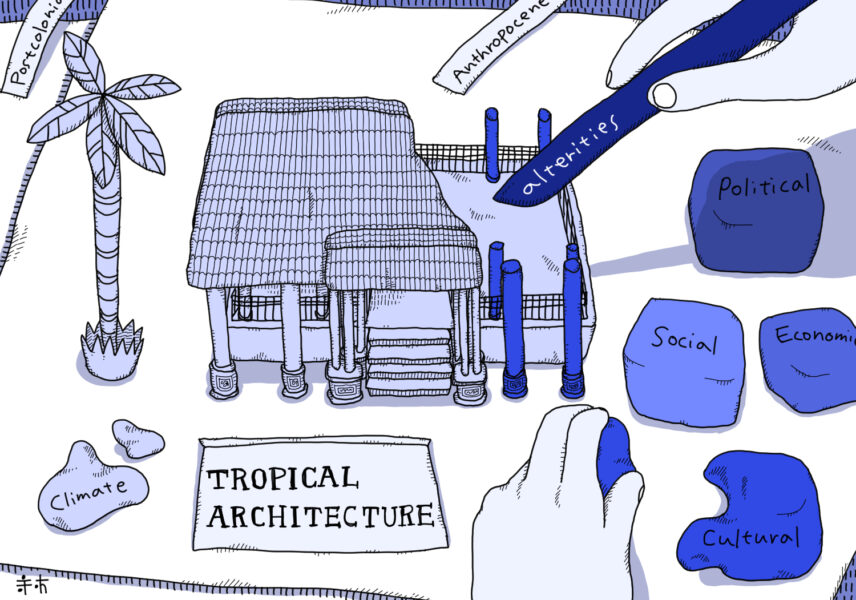

In discussions on tropical living, much emphasis is placed on enhancing comfort in hot and humid environments. Following Michel Foucault’s approach, Chang interrogates the underlying assumptions of such discussions by tracing the genealogy of tropical architecture. Since the “discovery” of the tropics by explorers in the 18th century, the prevailing discourse has linked tropical climates to various “problems,” including “delays in civilization, poor hygiene, and discomfort.” These ideas were shaped by then-influential medical theories such as (neo)-Hippocratism, miasma theory, and germ theory. For instance, Otto Königsberger, a pioneer in tropical architecture education in the 1950s, taught that tropical climates were physiologically disadvantageous for national development, drawing on the climatic determinism of geographer Ellsworth Huntington and others. He argued that science and technology could resolve the “problems” of the tropics.

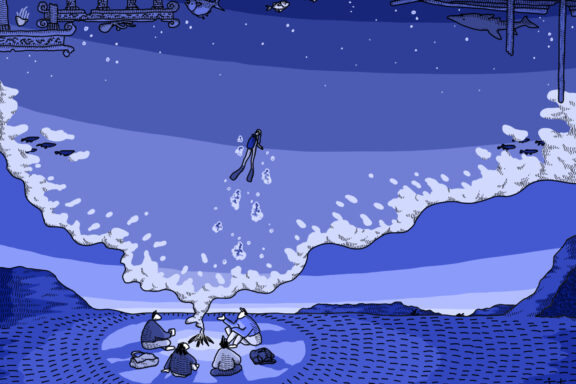

Employing actor-network theory, the book describes the spread of tropical architecture as a contingent, multifarious socio-technical process, akin to something spreading through an irregularly woven web. The nodes in the web are not political leaders or architects, but rather technocrats in the (post-)colonial network. With no architects during the early colonial period, civil engineers oversaw the construction and thus played a critical role. Chang also illuminates the significant roles played by objects and nameless people. Construction sites were heteronomous and heterogeneous, dependent on immigrants from China and India, whom the technocrats viewed as “careless and unskilled.” Projects also heavily depended on locally available building materials, such as shell lime and coconut husk.

Moreover, the book meticulously details the social, political, and cultural contexts overshadowed by climatic discussions. For instance, in anticipation of the Japanese army’s southward advance, the design of the British military barracks at the Changi Cantonment, completed in 1941, was influenced by miasma theory, which was championed by Florence Nightingale and prioritized ventilation with wide corridors and windows on both sides. The barracks also featured recreational facilities, including an air-conditioned cinema and a golf course. Simultaneously, Chinese immigrants nearby endured long working hours and limited access to medicine, despite suffering from tuberculosis and malaria, as well as consequent opium use and addiction to escape their hardships.

Techniques such as quantification, surveying, mapping, photography, and drawing were employed to govern these “unsanitary and unhealthy” populations. William John Ritchie Simpson, the founder of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, mapped tuberculosis deaths in shophouses for five years, attributing the disease to “poor living conditions” and insufficient sunlight and fresh air. His proposed solutions disregarded social determinants of health and involved regulating alley widths, directions, and roof angles.

Chang emphasizes that it is not merely the dissemination of technology that matters, but rather how the technology is inextricably linked to local sociopolitical situations and inevitably transformed through relevant actors and networks in the culture of post-colonial developmentalism. The same applies to public health. Tropical regions are viewed as unsanitary and unhealthy—a perspective rooted in colonial attitudes that persist today. The global health movement has consistently promoted the adoption of modern medical technologies in the Global South, often without considering the local contexts and factors that would inevitably transform them. These technologies, in turn, may change the very fabric of local communities in unintended ways. One instance in Indonesia is the family planning (keluarga berencana, KB) program, which was galvanized during the Soeharto regime. Technologies linked to KB, such as contraceptives, were introduced to Indonesia as part of the globalization of modernism. The World Health Organization praised the government for reducing maternal mortality; however, there were cases of forced sterilization. Importantly, KB methods and modernist ideas affected the discourse on familial relationships and gender roles in the country for decades afterward.

The mere existence of “tropical architecture” is peculiar, given the absence of a corresponding “temperate architecture.” The former does not refer to vernacular architecture, but rather a discipline or another “foreign technology” birthed from colonialism and modernism and then transformed through local context over time. This anomaly parallels the discipline of “tropical medicine,” which similarly emerged from and enforced colonial ideas. Reading A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture made me realize how closely intertwined the histories of architecture, medicine, and public health are.

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「建築と公衆衛生のあいだ」(山田千佳)