Kisho Tsuchiya (Southeast Asian Studies, Modern History)

When I was a 21 year-old undergraduate student, I had the special opportunity to work with the United Nations Electoral Support Team in East Timor (UNEST) for one year. I had idealistic expectations about international cooperation and was excited to work in Timor-Leste, which was being introduced as a kind of “laboratory” for peacebuilding, humanitarian aid, and democratization.

Upon arrival, I started conversing with people in towns and villages in Tetun through informal chats and accessed information circulating within UN agencies through its intranet. I began to realize that the image of East Timor and the UN that I had known from written information in Japan was significantly different from my on-the-ground impressions, common sense of the Timorese people, and the local reputation of the UN.

At the time, Timor-Leste was introduced to Japanese students as a “newly independent state liberated from Indonesian military occupation” and as a “successful example of UN peacebuilding.” However, not all East Timorese were content with the state and society after independence in 2002. The rapid changes led by the UN, while bringing about a new order and a democratically run state, also created social tensions in various sectors. Indeed, my sojourn in Timor-Leste was shortly after the riots of 2006, in which dissatisfaction exploded.

When I was working for UNEST, some Timorese continued the “independence movement” and resisted the UN. Information about such steadfast Timorese “veterans” and “gangs” boycotting elections often reached my office. According to them, the UN, which was supposed to have helped Timor-Leste “restore” independence, was instead a neocolonial power and therefore the struggle for independence continued.

For international aid workers like me, the contexts and meanings of such Timorese ideas and movements were completely incomprehensible. We discovered that the “laboratory of international cooperation” was still a site of anti-colonial struggle, and we were seen as colonial officers.1

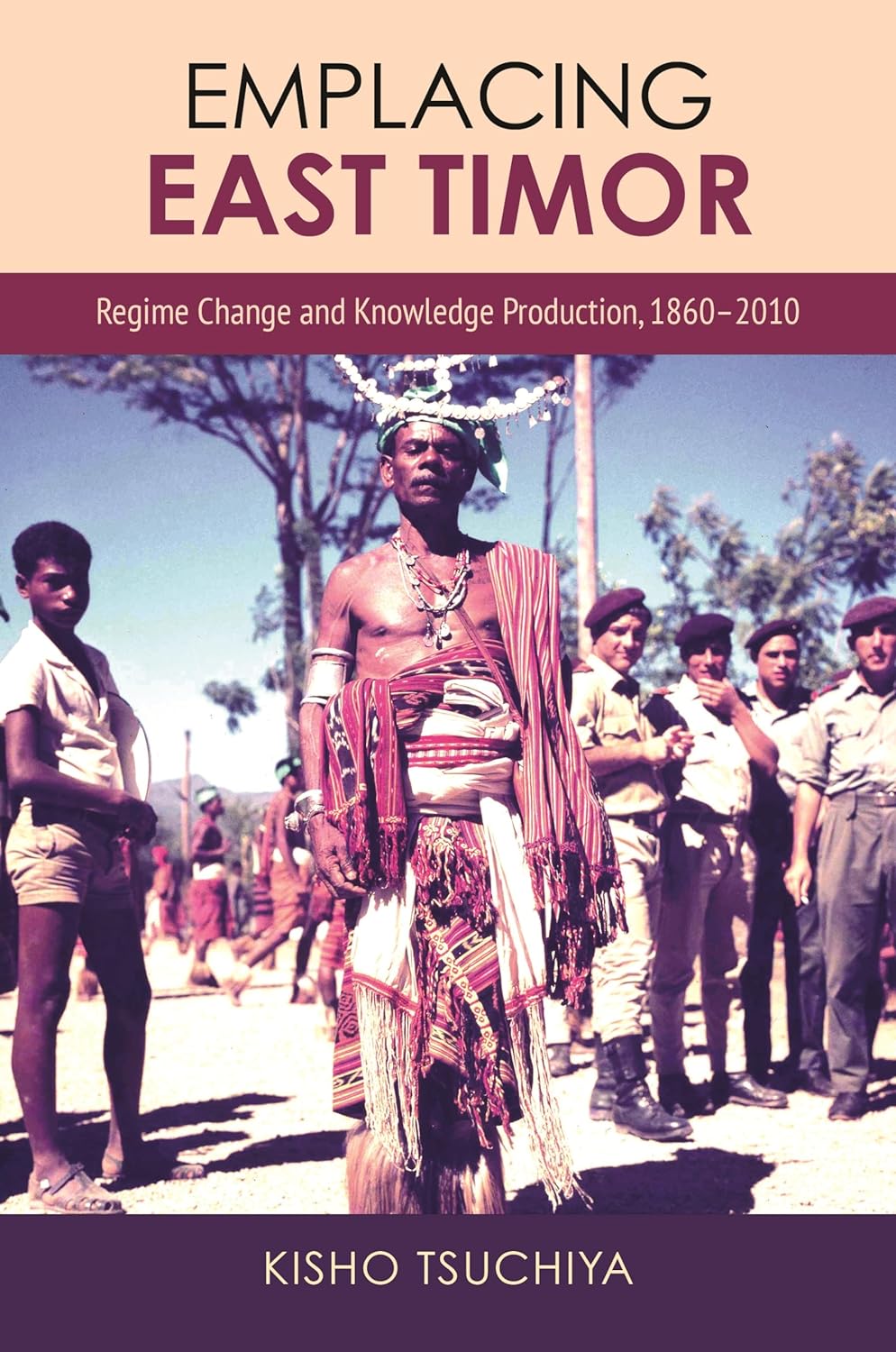

Against this background, I became interested in the process by which knowledge about specific places (such as Timor-Leste) is produced domestically and internationally, the human relationships and financial flows involved, the meanings of these places, and the experiences of the people living there. Emplacing East Timor: Regime Change and Knowledge Production, 1860–2010 (University of Hawai‘i Press, 2024) aims to address the dilemmas experienced by international aid workers, like my former self, by elucidating the modern and contemporary history of Timor Island as well as the various problems associated with knowledge production.

What is in the Title?

Emplacing East Timor refers to the historical actions and expressions that have given meaning to (East) Timor for various groups of people. In other words, I use the word “emplacing” to encapsulate the transformation of a seemingly empty space into a meaningful place. For many people living outside of Timor in the mid-19th century, Timor Island was merely a space. Today, however, it is clearly recognized as a place in the world. This is not least because wars and conflicts have been waged over this place, people have staged movements and occupied it, and researchers and writers like me have created discourses and ideas associated with it.

Why this Book?

During my stint as a UN staff member, no matter how many history books I read, I could not understand the myriad political debates or the contexts of the emerging tensions in the new nation. One reason for this was that prior research consisted of fragmented information and was highly politicized, serving particular audiences and political factions. Therefore, my initial aim was to provide a more comprehensive portrayal of Timor Island’s modern and contemporary history by integrating academic traditions from Portuguese-speaking countries, English-speaking countries, Japan, and Indonesia, while also introducing and critiquing various existing theories about (East) Timor.

To understand the various political ideologies expressed by the Timorese in their context, we need to know how these ideologies gave meaning to the place known as East Timor (or Timor Island) and how they justified their arguments by borrowing or opposing pre-existing knowledge. It is crucial to note that much of the knowledge they relied on was originally created by foreign authors, such as colonial scholars, who positioned “Timor” as a colony at the bottom of the Europe-centric world order. Hence, the book attempts to elucidate the genealogy of theories about (East) Timor as well as the global power relations and human networks behind them.

Finally, the book delves beyond power relations and individual expressions to analyze recurring political patterns, long-term changes, and the structure of knowledge production to reach, and convey, a deeper understanding of Timor’s history.

Findings

Some of the discoveries in Emplacing East Timor are explicitly stated for the reader, while others are merely implied. Here, I will introduce two main explicit findings.

The first finding is that so-called experts and spokespersons of various organizations, who claim to know the history and Timor, tend to handle information outside their field in a very careless manner and employ eccentric interpretations to advance their claims. For example, George Windsor Earl, who popularized the term “Indonesia,” wrote that “a single glance is sufficient” to distinguish between the Malay and Papuan races. Similarly, Alfred Russel Wallace, who is quoted more frequently than Earl, spent one night and two days in Kupang, Dutch Timor at the time, and boasted that simply by hearing Timorese women speak loudly, one could tell without seeing that they are not of the Malay race. From the perspective of scientific standards after the 20th century, their theories about the Timorese were merely personal impressions based on racialism. When Indonesia’s military occupation of Portuguese Timor became an international issue in the late 1970s, those involved in the international movement for East Timor’s independence quoted Wallace’s claim to argue that East Timorese were of the Papuan race and to prove that the war between Indonesia and East Timor was an “invasion by foreign powers.” In other words, the discourse of the human rights movement selectively used information based on racist impressions created during the colonial period. This book provides numerous examples such as these, exposing the farcical side of knowledge production.

However, the more serious discovery concerns the cycle of violent regime changes in modern East Timorese history, the long-term factors that form this cycle, and the impact these have on society and the production of knowledge. During the past 150 years of Timor Island’s history, a recurring pattern plays out approximately every 30 years: a large-scale conflict or war results in the loss of a significant portion of the population, power structures shift and are stabilized under a new regime, social tensions deepen again, violence re-emerges, and there is another regime change. The book’s conclusion argues that some of the factors that form this cycle of violence persist today. The international images of Timor—as colony, “the Cuba of Southeast Asia,” a site of human rights violations, a place of resistance movements, or a laboratory for international cooperation—are created as a backdrop for current events, often suppressing the long-term experiences, worldviews, and daily lives of the people living there. To consider the peacebuilding of East Timor, a new country born in the 21st century, from a long-term perspective, it is necessary to recognize recurring historical patterns and the responsibility of knowledge producers. In this sense, I wrote this book not only for students and researchers of history and area studies, but also for aid workers and young people who are aspiring to pursue international cooperation.

Note