Hiroshi Ishii (Maritime Archaeology, Modern Conflict Archaeology)

Chuuk is a state of the present-day Federated States of Micronesia. As one of the world’s largest atolls, it is a ring-shaped coral reef comprising nearly 250 large and small islands. Chuuk is in the western Pacific Ocean, about 3,400 kilometers southeast of Japan. It takes roughly 6 to 7 hours to fly to Chuuk from Japan via Guam. If you can imagine tropical islands east of the Philippines and halfway between Japan and Australia, that would be Chuuk.

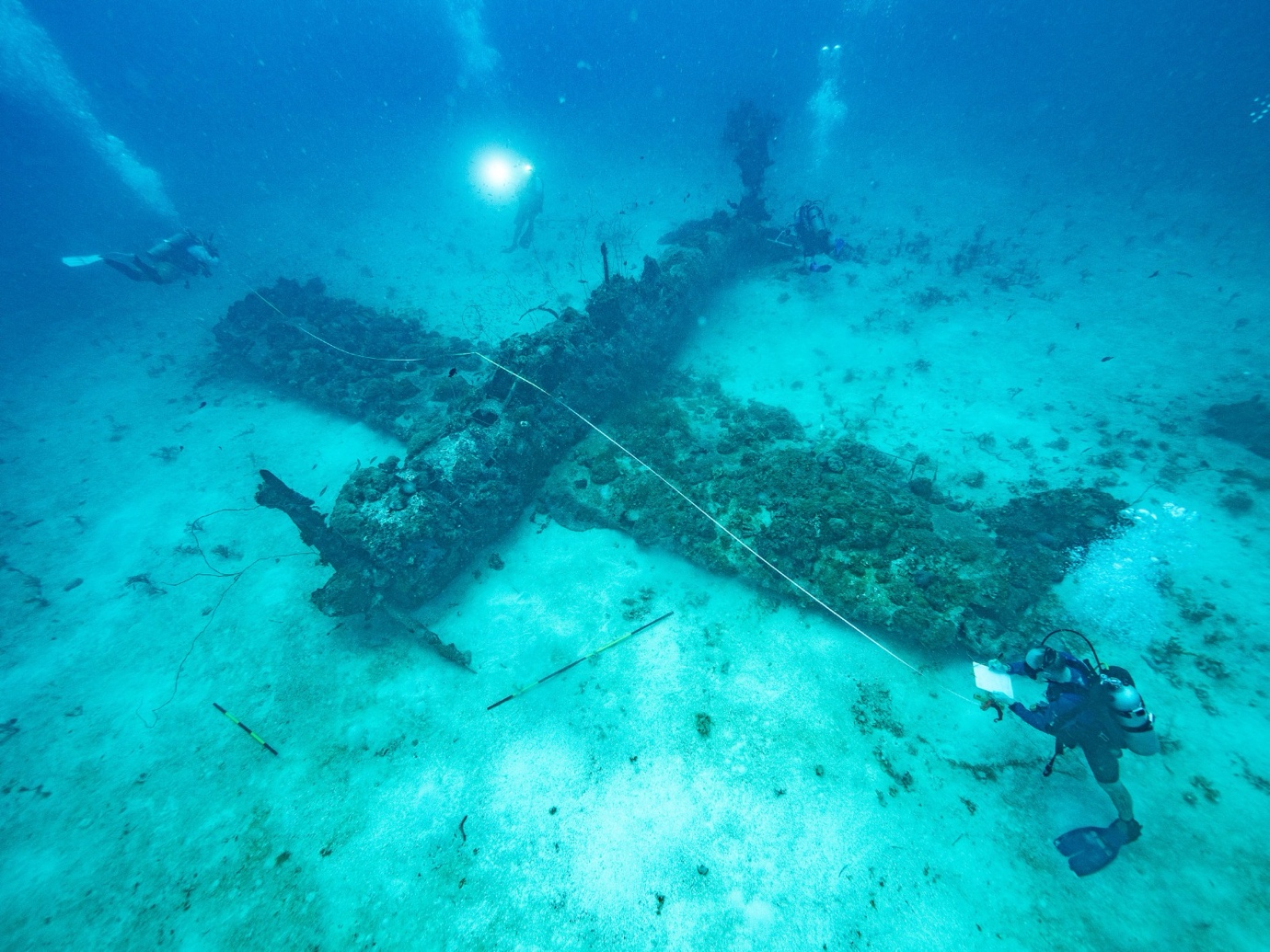

In July 2023, I participated in field surveys on Tonoas Island in the Chuuk Lagoon as part of a project funded by the Battlefield Preservation Program of the US National Park Service. The project assembled an interdisciplinary research team of experts in archaeology, cultural anthropology, marine biology, and other fields to uncover heritage associated with and impacted by World War II. At the end of 2024, the project team, led by Dr. William Jeffery of the University of Guam, released the interactive map “Tonoas, Chuuk (Truk) Lagoon during World War II.” The map identifies war-related heritage sites from Japanese rule on Tonoas (named Natsushima by Imperial Japan).

Chuuk: A brief history

People first migrated to Chuuk approximately 2,000 years ago (Intoh 1997), but in the sixteenth century, the atoll was “rediscovered” by the Spanish and became a Spanish territory. Following the Spanish-American War in 1898, the German Empire purchased the Chuuk and other islands from Spain, making them a German territory. In 1914, during World War I, the Imperial Japanese Navy occupied Chuuk without bloodshed (Kobayashi 2019), and it remained under Japanese rule until the end of World War II in 1945.

Under the Imperial Japanese administration, Chuuk was called Truk as part of the South Seas Mandate (Nan’yō). The various islands of Truk were given Japanese names, such as Natsushima (Summer Island), Harushima (Spring Island), Suiyōjima (Wednesday Island), and Takeshima (Bamboo Island).

As the war against the United States and Britain approached, Truk/Chuuk grew in geopolitical importance, and the Japanese developed it into a strategic naval base. The atoll played a significant role in supporting operations in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific until suffering devastating damage during the Operation Hailstone air raid from February 17-18, 1944. The atoll ceased to function as a military base and was subsequently isolated. Many of the Japanese ships and aircraft that sank during the raid remain on the ocean floor, and today these wrecks are a major tourist attraction, drawing divers from around the world (Jeffery 2007).

Remnants of Japanese Rule on Tonoas

In addition to the interactive website mentioned above, the project produced full-color English tourist maps of heritage sites distributed free of charge within Chuuk. Furthermore, English and Japanese bilingual information boards were created and installed at 11 locations on Tonoas Island. These materials help visitors, many of whom come to the island for recreational activities like shipwreck diving, develop a more profound interest in and understanding of the island’s war history and historical sites. Here, I introduce three historical sites from the Japanese era that remain in Tonoas, referencing the descriptions provided on those information boards installed at sites during the project.

Chuukese School: This building was used during Japanese times as a school for Chuukese students. After a fire destroyed the building on the hilltop above, it was used as the Truk Branch Office of the Japanese Territorial Government of the South Seas. Only Chuukese students would attend this school, and the tuition was implemented in the Japanese language.

There are two stone memorials. One down the hill is a memorial to MORI Koben. He arrived in Chuuk in 1891 and remained until his death in 1945, eventually becoming known in Japan as the “King of the South Seas.” His great-grandson, Manny Mori, was the 7th President of the Federated States of Micronesia from 2007 to 2015.

The stone pillar placed adjacent to the sports field has the heading “Truk Park”, the name of “Togoh Kichitaroh”, who was the temporary commander of the Nan’yō Islands garrison, and the date “in 1915, November 10th”.

Chuukese Hospital: Built by the Japanese in 1928, this was the only hospital in Chuuk open to civilians. During the war, the Japanese Army used it as their hospital, which had a capacity for 300 patients. The army also used the nearby Japanese public schools, which were turned into patient wards. The hospital was a facility where medicines were dispensed, and a small number of beds were available to Chuukese and Japanese patients—in separate areas. The remains of the Japanese garden near the building still contain Japanese plants.

Truk Shinto Shrine: A long series of concrete steps leads to this main Shinto shrine established in Chuuk. The shrine consisted of a small wooden building that was the location for the ceremonies conducted by a priest, the foundation measuring 30 x 24 feet. There were Japanese sentries at the base of the steps on the main road, and if Chuukese passed by without stopping and bowing, they were reprimanded and even beaten. Similar Shinto shrines were established throughout Micronesia. Chuukese and Japanese were compelled to come here with offerings and to listen to the priest. Chuukese considered the ceremonies to be more like Japanese propaganda than religious events.

The project website introduces additional sites remaining on Tonoas, including a Japanese Navy headquarters and a submarine base.

When I visit these war heritage sites, I feel the weight of history that can only be conveyed by physical objects that have survived from the past to the present. I find myself asking the simple questions: Why did the Japanese expend so much effort to expand their territory to such distant southern islands? What did the Japanese bring to this island? No matter how much we understand the history of territorial expansion and war in our heads, these are feelings that only the actual ruins can evoke, and they may be reverberations of the ideologies that the Japanese people believed in, such as those espoused by the former Empire of Japan and the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

Beyond Physical Heritage: Memories Remaining Overseas

During both World Wars, states mobilized their military and civilian populations in national undertakings to wage war against one another, as embodied by the term “total war.” The impacts of these modern wars extended far beyond traditional battlefields, reaching from densely populated cities to islands in the Pacific, such as those of Chuuk. These islands became territories of the great powers, greatly affecting the people who lived there.

In modern conflict archaeology, which involves the study of war sites and artifacts, attention tends to focus on military aspects, such as weaponry and military history. However, the memories of war passed down by civilians and those who lived under foreign rule are equally important. In this regard, this research project by the University of Guam is groundbreaking, as it actively incorporates oral history by gathering stories directly from local people in the field. This approach is reflected in our website, which includes interviews with locals. Please visit our website “Tonoas, Chuuk (Truk) Lagoon during World War II” and take a moment to engage with the history shared between Japan and Chuuk.

References

Intoh, Michiko. (1997). Human Dispersals into Micronesia. Anthropological Science. 105. 15–28. DOI: 10.1537/ase.105.15.

Jeffery, William. (2007). War graves, munition dumps and pleasure grounds: a postcolonial perspective of Chuuk Lagoon’s submerged World War II sites. PhD thesis, James Cook University. DOI: 10.25903/b4q7-5k51.

Kobayashi, Izumi. 2019. 南洋群島と日本による委任統治 [The South Sea Islands and Japan’s South Seas Mandate]. 島嶼研究ジャーナル [The Journal of Island Studies]. 9(1):2019.11, p.6-27. https://ndlsearch.ndl.go.jp/books/R000000004-I030098285

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「チューク諸島、トノアス島(旧トラック島、夏島)の戦争遺跡」

(石井 周)