I was born in an old New England seaport and have lived near the ocean almost my entire life. The history of my hometown’s harbor—Salem, Massachusetts—is one of far-flung connections to Arabia, Sumatra, and China carried on the decks and in the holds of wooden ships that crossed the Atlantic to enter into the complex commercial and cultural circulations of the Indian Ocean in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The experiences on those voyages shaped a local culture that while in many ways peculiarly provincial, also incorporated a familiarity with diverse distant ports of call across watery stretches of the world.

My early fascination with that maritime past has shaped the course of my studies for decades. Settling here in Kyoto a few years ago I wondered if I would eventually slip into a landlubber’s view of the world, at least between shipping out for fieldwork in the islands of the Maldives and Indonesia. To date, however, that has not been the case. My office at CSEAS looks out onto the Kamogawa and as I walk along stretches of it to and from work, I have come to realize that even this far upstream one can still feel connections with more watery parts of the world stretching back through time.

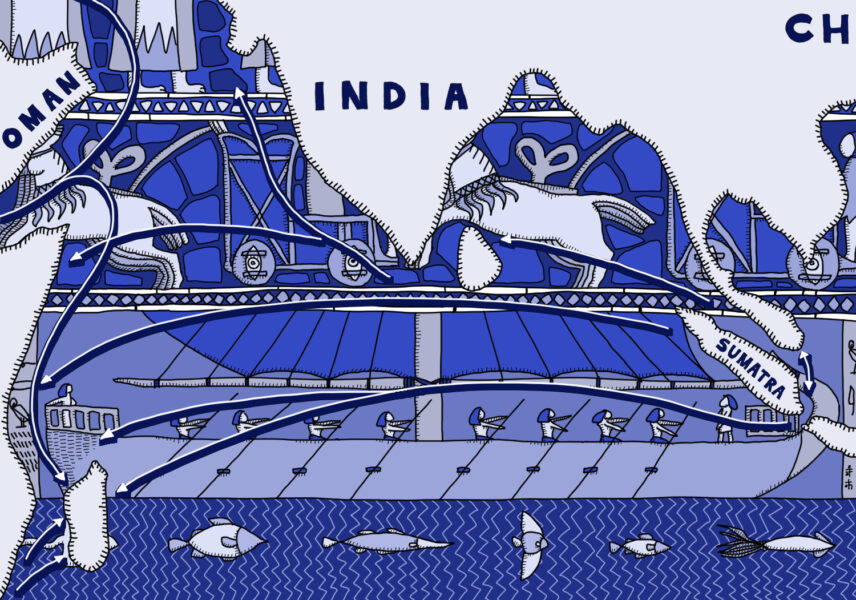

Such historical imagination shapes the magisterial work of Philippe Beaujard on The Worlds of the Indian Ocean (Les Mondes de l’océan indien, 2012 / English translation, 2019). Covering more than three millennia in the course of two massive volumes, Beaujard’s work posits a long view of global history taking shape across a plurality of interconnected zones linked through dynamic engagements with the Indian Ocean. His coverage of each period then has significant sections on an expansive range of geographic areas that he presents as integrated within his capacious conceptualization of the ‘worlds’ of the Indian Ocean: Egypt, the Near East, Persia, India, Southeast Asia, China, Arabia, East Africa, and Madagascar.

For me, Beaujard’s work serves as an incredibly rich example of historiographic world building, creating a thick sense of connection over vast swathes of time and space through the erudite exposition of well-selected and masterfully deployed examples. In chronicling the increased size and number of junks built over the twelfth to thirteenth centuries, for instance, he highlights the fact that while built in China those vessels were assembled from materials sourced elsewhere: coir rope from the Maldives and other Indian Ocean islands, hardwood rudders from Southeast Asia, and wooden planks from Japan. From my perspective as an historian in the habit of getting my feet wet tracking down source material, recognition of and engagement with such complex maritime pasts brings a certain comfort in thinking that the clear shallow stream running past my office window can yet carry me down to deeper oceans of imagination.

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. »

「想像力の深海に潜る」(R. マイケル・フィーナー)