Miriam Jaehn

(Refugee and Forced Migration Studies, Asian Studies, Social and Cultural Anthropology)

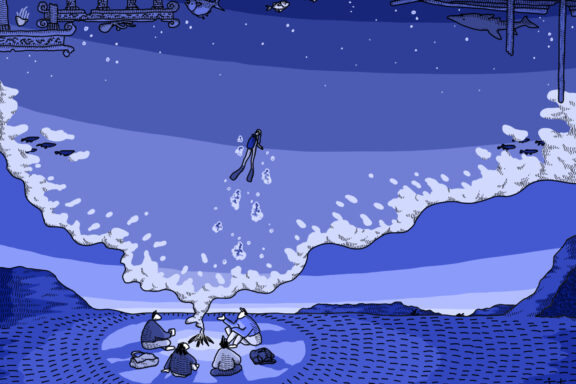

Working at CSEAS, the seasons of Kyoto allow me to make my office outside of office. Escaping the monotony of cold concrete walls, I regularly find myself sitting under the Sakura and Momiji trees lining the Kamogawa. As I seek protection in their shade and watch the shallow waters of the river flow steadily, my mind starts wandering back to the Andaman Sea and the sweltering heat of South and Southeast Asia’s borderlands: I smell the Rohingya food being cooked, I hear the mix of languages being spoken, and I watch the tides of solemn calm and industrious busyness of Rohingya families’ rebuilding their lives in displacement.

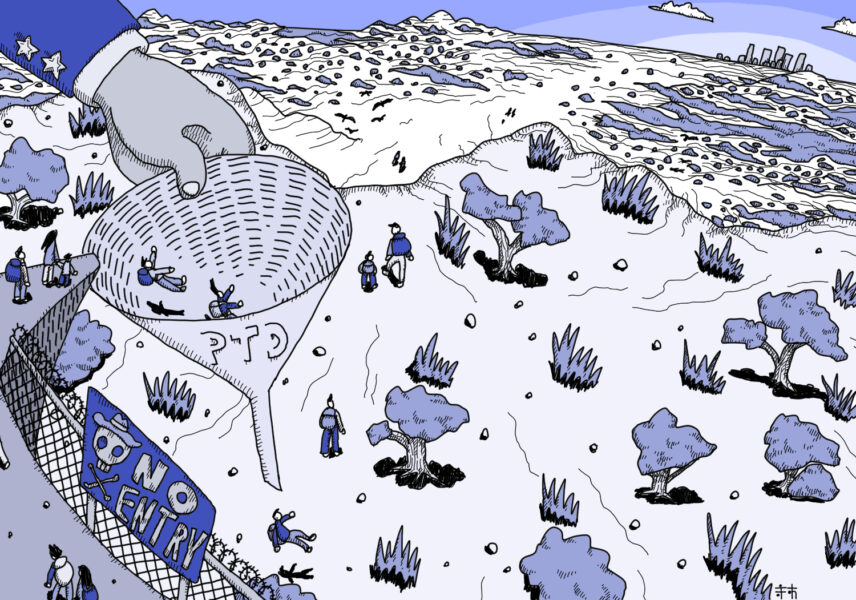

In preparation of working with Rohingya who had to flee their homeland, I read Jason De Leon’s Land of Open Graves: Living and Dying on the Migrant Trail (2015) in which the author traces Latin American migrants’ journeys back and forth across the Sonoran Desert. For his book, De Leon uses anthropological storytelling and photography to narrate migrants’ stories, whereby he also pays attention to the material traces they leave behind on their routes through the desert. As such, De Leon values migrants’ so-called trash as artifacts that document, materialize, and make migration history. He further narrates the story of Maricela whose corpse he found in the desert. Like many other migrants, Maricela fell prey to what De Leon calls “necroviolence.” While Mbembe’s necropolitics describes how certain bodies become subjugated to living closer to death than life (2003), De Leon’s necroviolence expresses the very corporeal mistreatment of migrants through US immigration policies and practices.

De Leon argues that the US consciously instrumentalizes the Sonoran Desert as a ‘natural’ border to keep ‘undesirable’ migrants out, using its hostile terrain to outsource migrants’ mistreatment. As migrants attempt to cross the border through the desert, they do not only suffer physical and mental harm but they may die without their corpses ever being found, resulting in “the complete destruction of [their] corpse [which] constitutes the most complex and durable form of necroviolence […]. The lack of a body prevents a ‘proper’ burial for the dead, but also allows the perpetrators of violence plausible deniability” (De Leon 2015, p. 71). For Latin American migrants and their families such necroviolence constitutes a violence that lasts postmortem as it confuses rituals of mourning, delays processes of grieving, and raises concerns regarding migrants’ afterlife. In the end, migrants’ families often wait, worry, and hope in despair over their relatives’ fate for years.

De Leon’s work resonates in the stories of many Rohingya who lost family members to persecution and flight: In Arakan, on the Andaman Sea, and in the mountainous jungles of Thailand and Malaysia. But while De Leon centres such experiences in his work, I hope to focus on how Rohingya, while condemned to float on land and sea, work hard to resist and circumvent such necroviolence, fighting to root themselves in time and space.

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. »

「川と海のほとりにて」(Miriam Jaehn)