Jean-Pascal Bassino (Economic History)

Christopher Goscha, professor at the history department of the University of Quebec à Montréal, is a leading historian of 20th century Vietnam. He is the author of twelve books and numerous articles. His extensive knowledge of the historiography and archives in French, English and Vietnamese has enabled him to contribute in a decisive manner to the renewal of the analysis of social and political conditions leading to the end of colonial rule. His most recent book published in 2022, titled The Road to Dien Bien Phu, he proposes an analysis of the first war Vietnam that is also known as the Indochina War (1945–1954).

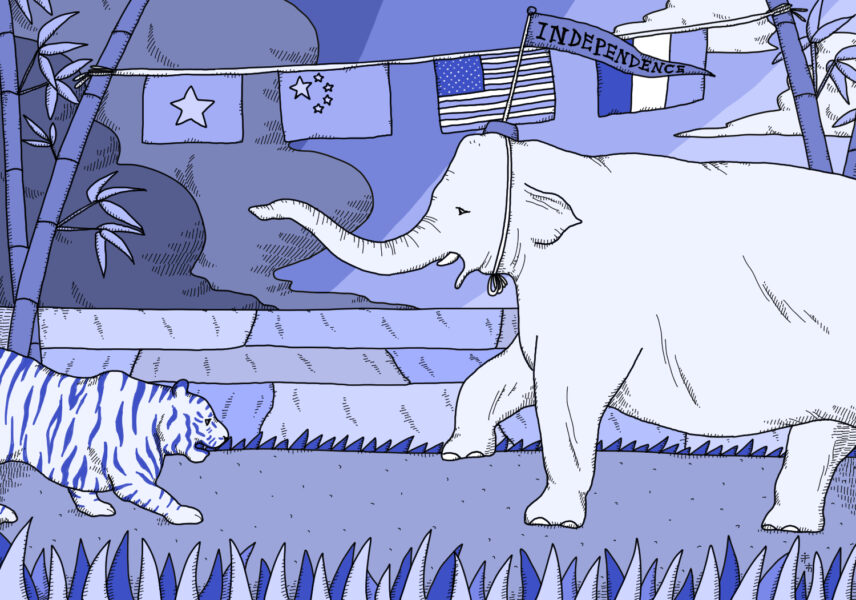

His monograph includes an investigation of the role of economic factors in the success of the Viet Minh against the former colonial power and their local allies, supported by the United States, at first reluctantly but more massively towards the end of the conflict. While the confrontation was initially an asymmetric conflict waged by an insurgency employing mostly guerrilla techniques, it ended in 1954 in Dien Bien Phu in the first defeat of an American ally in a conventional battle of the Cold War period, prefigurating the humiliating defeat of the United States during the fall of Saigon in 1975.

A number of economic historians have analyzed the economic determinants of the outbreak of major conflicts and of the role of state capacity to achieve supremacy in conflict requiring massive industrial output, in particular World War I and World War II (e.g. Broadberry and Harrison 2005). In addition, several studies have also investigated how the resources of occupied countries have been mobilized to finance military operations (e.g. Huff and Majima (2013) on the Japanese occupation of Southeast Asia). In comparison, a few studies have been focused on asymmetric wars, in part due to difficulties to access information on one of the protagonists.

Although it is not his primary objective, Christopher Goscha’ book offers a comprehensive view of the role of economic factors in Indochina war. This includes in particular the role of cross-border trading Southeast Asian networks enabling the smuggling of weapons during the first years of the war, the rise of the Viet Minh archipelago state and its financial revenues and expenditures, the US and Chinese aid after 1949, and the mobilization of resources such rice to be brought to the troops in the highland area of Dien Bien Phu, in the final phase of the war.

These factors should not be overstated. It is well known that the southern part of Vietnam (called Cochinchina by the French colonial administration) had the by far highest average per capita income before 1940 and a much higher level of income and wealth inequality than the central and northern part of the country. But it was the area where the Viet Minh was the weakest. The political economy of the War is remarkably described in chapter 9 titled Rice and War that shows how the Viet Minh officials were perfectly aware of the importance of what they called General Rice. The documents cited indicate that the French military command had a similar perception.

The agricultural sector provided a major part of the revenues financing the Viet Minh military operations through the land tax collected in the areas under their total or partial control. The peasantry was heavily pressured, but the mobilization of conscripts for military operations and the logistics had to be limited to what was compatible with rural living standards at least slightly above subsistence level in these areas. In the rural areas they did not control, the systematic destruction of rice stocks during night raids, including at the village granaries, put the peasants between the hammer and the anvil, as noted in a French military report, and forced the colonial authorities to dedicate a sizable part of their military manpower to static and logistic tasks. The fact that the option of scorched earth strategy in Viet Minh areas, at some point considered, was eventually rejected suggests that the French military command realized that long-term cost would largely exceed the short-term benefit, and that it was unlikely to affect the issue of the conflict.

References

Broadberry, S. and Harrison, M. (Eds). 2005. The Economics of World War I. Cambridge University Press.

Goscha, C. 1999. Thailand and the Southeast Asian Networks of the Vietnamese Revolution (1885–1954). Richmond: Curzon Press.

Goscha, C. 2022. The Road to Dien Bien Phu: A History of the First War for Vietnam. Princeton University Press.

Huff, G. and Majima, S. 2013. Financing Japan’s World War II Occupation of Southeast Asia. The Journal of Economic History 73(4), 937–977.

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)