I came to CSEAS in April 2024 after leaving the Graduate School of Language and Culture, Osaka University. I study the modern history of Myanmar, particularly its transition from colonial rule to a nation-state.

As is typical for those in area studies, I am often asked, “Why are you studying Myanmar?” My personal journey with Myanmar began during my undergraduate years when I chose to major in Burmese, the official language of the country. This decision was influenced by the country’s emerging status as “the last frontier of Asia” and my desire to explore something new.

While studying Burmese throughout my undergraduate and master’s years, I learned about the linguistic and cultural diversity of Myanmar. At the same time, I encountered many narratives related to national unity. In particular, during the ceasefire negotiations between the Myanmar military and ethnic armed organizations of 2016 and 2017, newspapers and SNS actively advocated a return to the “union spirit” and “national unity” present at the time of independence.

My interest lies in the very act of “writing history” in this way. Historical narratives are born in their context and reference each other. However, we are often unaware that histories are written within such contexts and with a particular intention. As a result, we may conveniently interpret certain events to reinforce a narrative’s argument, or we may essentialize contemporary historical narratives.

For example, from the 1930s to the present, various narratives have been created regarding the establishment of a federal system in Myanmar. My research has focused on political activists who, from a minority position, demanded the establishment of a federal state to ensure both local autonomy and national unity. Despite their demand, the contemporary official historiography of Myanmar portrays them simply as ethnic minority politicians who contributed to the establishment of the nation-state, thus imposing a contemporary perspective onto past events.

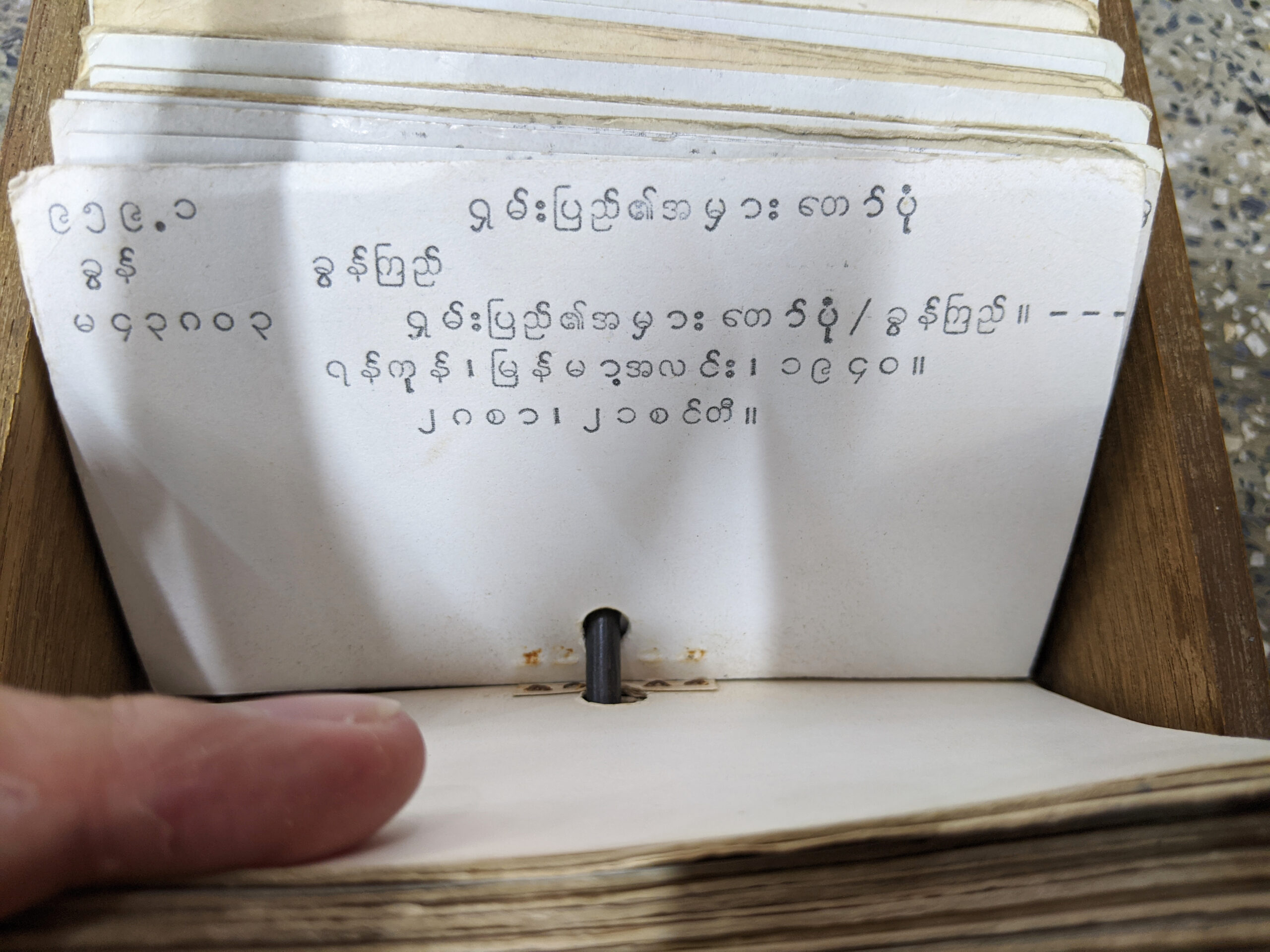

(December 2019, photo by the author)

When, under what conditions, and why is history written? To probe these questions, I read colonial administrative documents and postwar publications of Burma, especially memoirs. When I first began my research, my highest priority was placed on reading the original text as faithfully as possible without any annotation. Of course, it is still essential, but not enough for the study of narratives. I am now always conscious of the author and the intended audience, the historical background and motivation for writing, and the form in which the written material is transmitted (the language, medium, publisher, size, price, number of copies, and method of distribution).1

I plan to continue to analyze Burmese publications, taking advantage of CSEAS’s wealth of vernacular materials, and begin to compare the process of creating national integration narratives in Myanmar with neighboring countries in Southeast Asia and South Asia. I am eager to engage in dialogue with a variety of researchers amid the interdisciplinary environment of the Center.