Genta Kuno (Area Studies, Urban Studies)

It was dry season in Jakarta. I found myself heading to one of the city’s most infamous prisons with two friends. When our turn came, a warden handed us lanyards and stamped our hands with a UV mark. Inside the visitation area, mats were laid out, forming a communal sitting area where visitors and inmates mingled freely. As more people trickled in, the helper inmates shuffled around, adding more mats. After a while, the man we had come to see, whom I call here Ahmad, arrived, clutching his visitation letter.

Outside, Ahmad’s life was precarious, defined by what some might call petty crime and substance addiction. Inside, however, he said things were different, without calling them better or worse. He had the opportunity to meet big figures—such as a notorious gang leader and a former high-ranking police officer sentenced for a murder—who he never would have encountered outside. The fights he got involved in were no longer purely personal, but instead tied to ongoing tensions among inmates revolved around territorial control in cellblocks. To compete against other groups, he joined inmates from Central and West Jakarta who had formed an alliance called Barpus (an acronym for Barat=West and Pusat=Central).

The dynamics of Indonesia’s prison culture are vividly captured in the introduction of Joshua Barker’s State of Fear: Policing a Postcolonial City (2024). Barker observed a prison in Bandung in the mid-1990s. Unlike my experience confined to the designated visitation area, he managed to access the cellblocks themselves. Echoing the stories I heard from Ahmad, he recounts that cellblocks operated under the de facto control of inmates.

Fear is the dominant impression when visiting a prison. Like Barker, my friends and I too were, simply, scared. From the panoptic architecture and surveillance technologies to the strict procedures, many features of the place, and of the experience inside it, seem intentionally designed to elicit unease. On top of this is the knowledge of inmate territories in the prison. Barker describes this peculiar fabric of fear as a collision between two worlds. In one, there is the opaque realm of criminality and territoriality, while in the other, there is the translucent sphere of bureaucratic policing and surveillance. Inhabitants of both worlds stake a claim to what can be called “security” underpinned by fear. This collision transcends the prison walls to shape societal structures, as described in the book’s exploration of everyday aspects of policing in the country across time.

Back in town, Ahmad was known as a local thug in an urban kampung, surviving on informal parking jobs and occasional drug deals. The parking crew he joined respected a figure closely tied to the head of the neighborhood association. While the crew controlled parking spaces near the main street, frequently clashing with thugs from a rival neighborhood, the neighborhood head collected security fees from businesses along the street. As Barker might describe, this dynamic reflects the neighborhood as a territorial power intertwined with the authority of street ruffians. Such territorialities are inherently impermanent, requiring continuous “acts of care.” These acts may range from enhancing recreational function, such as constructing ornamental gates or crafting communal benches, to essential acts, which revolve around keeping night watches. People often develop a strong sense of belonging to these local territories, which offer a legitimacy that surpasses other umbrellas of affiliation, such as citizenship, ethnicity, or political group. This book reminds readers that there is much more to uncover within the worlds full of obscure territories.

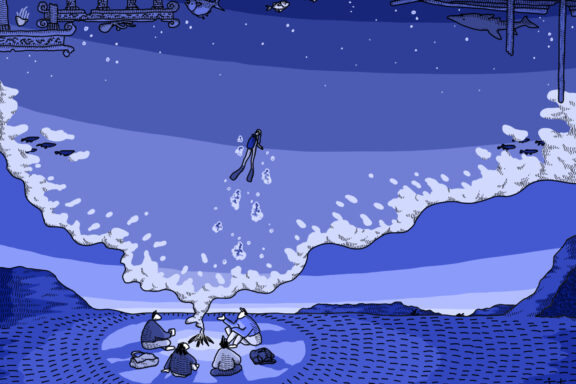

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)