Majid Daneshgar (philology, orientalism, and Islamic studies)

There are still many documents and materials from Southeast Asia kept in private and public libraries which have yet to receive the attention they deserve. Now, I would like to introduce one more item pertaining to both Muslim and non-Muslim materials, originate from the Buddhist heartland of Southeast Asia in the contemporary era.

There is a mysterious cardboard scroll tube (Classmark: “I.1”) in the Library of Professor Yoneo Ishii (石井米雄) (1929–2010) at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, Japan. Although the scroll tube is partially covered by a painted bookplate entitled “Historical Maps of Chiang Mai,” it does not contain anything about modern-day Thailand. Instead, it is full of different and intriguing materials from Burma (Myanmar), which are described in the present piece of work. These materials can be divided into three categories; while two of them (A and C) are merely in Burmese, one of them has a Muslim Burmese background (B).

A) The first rolled material is a picture of a Burmese Buddhist monk holding a stick, drum and traditional fan. He was, according to a note, photographed on 26 December 1993.

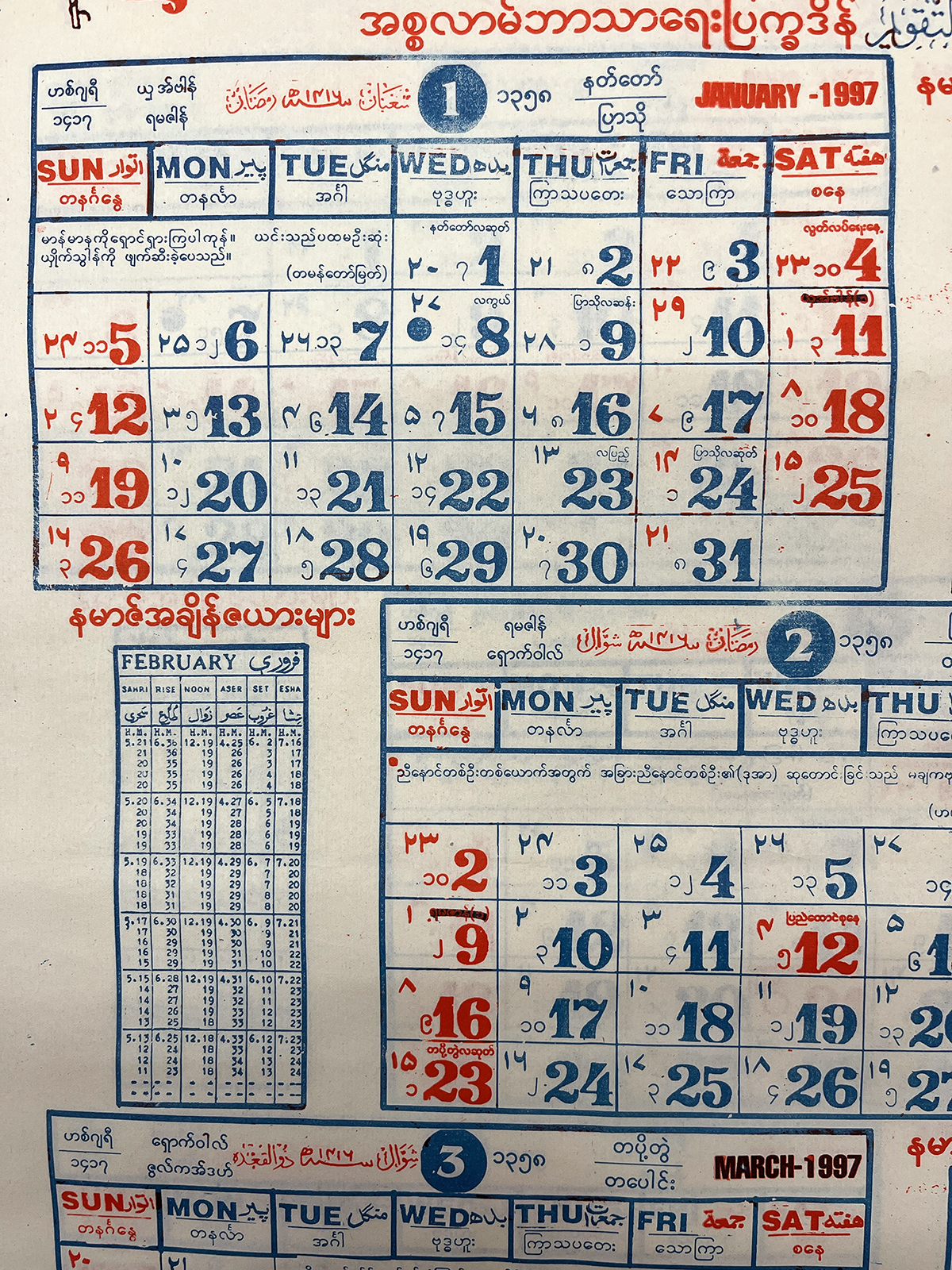

B) In contrast to the previous item about Buddhism, the second one is produced by one of the Muslim associations in Yangon. It is a 1997 (1317–1318 AH) wall calendar. The opening page is illuminated, showing the first chapter of the Qur’an in Arabic, along with its Burmese rendition (ဥရသွလီပါသိတယ်/ အဖွင့်ကဏ္ဍ) by a local maulavi who was probably in close contact with local madrasas.[1] The second page begins with the first month, January 1997. The striking point is not about its inclusion of Islamic calendars (al-Taqwim; al-Tawarikh; e.g., Sha‘ban and Ramadan) but its references to Islamic names of the seven days of the week. Instead of using Arabic-Persian scripts for Burmese days —like what used to be practised in Malaysia and Indonesia for centuries (e.g., Jawi and Pegon)—, Burmese Muslims have used Urdu alternatives. For instance, they offer two different names of တနင်္လာ and پیر for Monday, or အင်္ဂါ and منگل for Tuesday (Fig 1). Even dates are shown with Arabic, Urdu and Burmese numerals.[2] This could also be related to what was produced in local madrasas, those which “choose to adopt either Burmese or Urdu as their language of instruction […], along with reading the Qur’an and the traditions of the Prophet (Hadiths)”.[3]

This document demonstrates to what extent South Asian Islam had influence on the Buddhist world of Southeast Asia. This is despite the fact that most of our knowledge about the relationship between the two geographical regions is chiefly limited to previous travel reports and old materials, in which the role of Indian Muslims, Persians and Arabs (and their descendants) are highlighted.[4] A recent discovery also sheds light on the first extant account about the cultural activities of Persians from Isfahan and India in Burma and Thailand in the mid-seventeenth century.[5] One may wonder whether scholars can discern the origins of modern transregional influences (viz., based on item B) in historical travelogues and manuscripts. Further, unrolling such Muslim materials from Southeast Asia, as part of the library of a renowned Japanese Southeast Asianist may reveal how essential it is to explore historical relationships between Western and Eastern Asia; the more we learn about one, the more we find out about the other.

C) Another 1997 calendar, only in Burmese and produced by the Yangon University’s Department of Zoology to promote the legacy of different departments and academic societies, including the “Shan Literary & Cultural Committee”. Every page contains portraits of a male and female graduates and/or students studying in various academic fields. A few calendars are also printed in the Li Shaw region, Kyaing Tong.

Notes

[1] On the origin of Islam in Burma (Arakan and Mottama), see: Mohammaed Mohiyuddin Mohammed Sulaiman, “Islamic Education in Myanmar: a case study,” In Dictatorship, Disorder and Decline in Myanmar, eds. M. Skidmore and T. Wilson (Canberra: The Australian National University E Press, 2008), pp. 177–191.

[2] But Arabic scripts are used to introduce Muslim calendars and months.

[3] Mohammaed Mohiyuddin Mohammed Sulaiman, “Islamic Education in Myanmar,” p. 179. To read further about the influence of Urdu Muslim literature in Yangon, see Judith Beyer, Rethinking Community in Myanmar: Practices of We-Formation among Muslims and Hindus in Urban Yangon (Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2024).

[4] To read about post-eighteenth-century reports, see: Arash Khazeni, The City and the Wilderness: Indo-Persian Encounters in Southeast Asia (California: University of California Press, 2020).

[5] See the forthcoming work by Majid Daneshgar, “A Persian Shiʿi Anthology Circulating in Patna, Dhaka and Siam in the Seventeenth Century: A Lesser-known Ship of Persians to South-East Asia,” In Iran and Persianate Culture in the Indian Ocean World, edited by A. C. S. Peacock (London: Bloomsbury, 2025), pp. 249–260. This study deals with an anthology produced earlier than the well-known Ship of Suleiman which arrived in Siam in the late seventeenth century.