Chika Obiya (Modern History of Central Asia, Central Asian Area Studies)

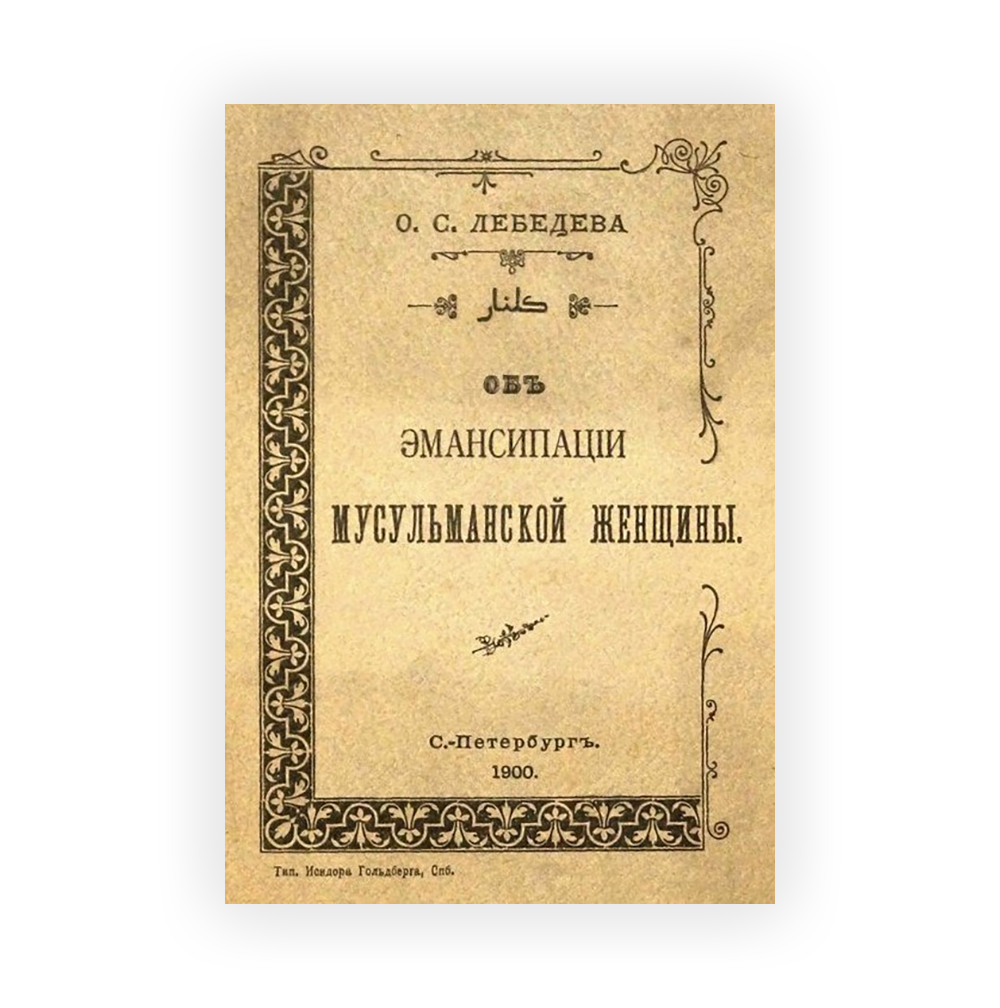

Although my primary area of expertise lies in the modern and contemporary history and area studies of Central Asia, particularly Uzbekistan, the following is about a research theme that ventures beyond that scope. While exploring the discussions and discourses surrounding Muslim women in Central Asia under the rule of the Russian Empire during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, I came across a Russian woman named Olʹga Sergeevna Lebedeva (1854–after 1912?), who authored a work titled On the Emancipation of Muslim Women (published in St. Petersburg in 1900). As I read this book, investigated the individuals and references mentioned within it, and gathered information about Lebedeva’s life and the people she interacted with, I unexpectedly uncovered a web of discussions advocating for improvement in the education and conditions of Muslim women, advancement of their status, and their ultimate emancipation. These debates spanned across the Russian Empire and the broader Islamic world and shed light on the nature of Oriental studies as an imperial academic discipline.

Who Was Olʹga Lebedeva?

Sometimes referred to as “Russia’s first female Orientalist,” Lebedeva is credited with being the first to introduce Russian literature to the Ottoman Empire through her translations into Turkish (Figure 1). She was born into a wealthy noble family in Kazan Province of the Russian Empire and later became the wife of the mayor of Kazan, the capital of what is now the Republic of Tatarstan within the Russian Federation. She was also the mother of six children.

In Kazan, a city that was not only an important administrative center of the Russian Empire, but also a cultural hub for the Turkic Muslim Tatar community, Lebedeva developed an interest in the Tatar language. This interest led her to study Tatar and other Turkic languages, as well as Persian, under the guidance of a prominent Tatar intellectual. Eventually, she developed a passion for Oriental studies, going so far as to audit classes at the Imperial Kazan University, which had not yet opened its doors to women. Her academic debut came with the publication of her Russian translation of the 11th-century Persian literary work Qābūs-nāme (Mirror for Princes), in 1886.

In 1889, Lebedeva attended the International Congress of Orientalists held in Stockholm, where she met Ahmed Midhat (1844–1912), a prominent figure in the Ottoman Empire’s publishing and intellectual circles. Midhat was deeply impressed by Lebedeva’s fluent Turkish and extensive knowledge, and the two formed a strong rapport (Figure 2). In the autumn of 1890, Lebedeva visited Istanbul, bringing several of her translations of Russian literary works with her, which were published one after another in Midhat’s newspaper Tercümân-ı Hakîkat (Translator of Truth). Lebedeva thus became widely known in Istanbul as the translator Gülnâr Hanım (Madame Gülnâr)—Gülnâr being her Turkic pen name—and was awarded the Order of Charity, Second Class, by Abdülhamid II, the reigning Ottoman Sultan (Figure 3). Through Midhat, she also connected with Fatma Aliye Topuz (1862–1936), the first Turkish female novelist who authored critical essays such as Muslim Women (1891) and Biographies of Great Muslim Women (1899–1901). For the next four years (1891–1895), Lebedeva spent every winter in Istanbul.

In Russia, Lebedeva founded the Society of Oriental Studies in St. Petersburg in 1890. She is also known for petitioning the Ministry of Internal Affairs in 1893 to establish a secular school for Tatars and to publish a bilingual Tatar-Russian newspaper to promote the education of Tatars.

In this way, Lebedeva was vigorously active—across borders—in both text-based work, such as translating literary works and reading and translating Oriental historical texts, and social action, such as organizing the Society of Oriental Studies and supporting Tatar education (Figure 4).

Interpreting Lebedeva’s Work On the Emancipation of Muslim Women

The work, based on a report that Lebedeva made at the 1899 International Congress of Orientalists, was intended to challenge the colonialist discourses of disdain and discrimination against Islam and Muslims that were prevalent in Europe, including Russia, at the time (Figure 5). At its core was the assertion that “returning to the teachings of the Quran and the Prophet Muhammad reveals that Islam inherently advocates equality between men and women.” Let us refer to this as the “Islamic discourse on the equality of men and women.”

Lebedeva recognized the dire situation of Muslim women at the end of the 19th century, describing it as one of extreme misery in which women were subjugated to men and denied their dignity as human beings. She presented examples of outstanding Muslim women in history who had been as active as their male counterparts, using these examples to argue for the equality of men and women in Islam. However, she noted that this equality had regressed since the 10th–11th centuries during the Abbasid Caliphate, and false doctrines that denied women education and equal rights with men had become widespread. Lebedeva insisted that the West ought to help Muslim women reclaim their historical right of equality with men and achieve a way of life that aligns with both Islam and modern civilization. She proposed the following three fundamental principles:

- Islam does not, in any way, hinder women from being equal to men.

- To introduce Western civilization to the East and promote integration with it, organizing a Society of Oriental Studies is essential.

- Efforts must be made to improve the education of both Muslim women and men by establishing schools for boys and girls and appointing teachers trained in Western education.

This work circulated to some extent in various parts of the Russian Empire and is said to have influenced a portion of Russia’s Muslim population, which was estimated to number from 15 to 20 million at the time. The work was later translated into French in Cairo and Turkish in Thessaloniki.

The Spread and Connections of the Islamic Discourse on the Equality of Men and Women

The arguments for the emancipation of women that Lebedeva referenced and supported were not those of the radical women’s liberation movements led by Russian intellectuals aiming for female independence. Instead, they were discussions on the equality of men and women in Islam developed by Western-educated Muslim intellectuals from various regions. Lebedeva played the role of a hub, connecting these discussions to Russia and Europe through translation.

Her arguments for equality in Islam were likely shaped within the context of direct and indirect connections with, at least, the following individuals. First, as mentioned earlier, Ahmed Midhat and his protégé Fatma Aliye of the Ottoman Empire were key. Midhat promoted the advancement of women in Turkish society in general and in and the literary field in particular. With Midhat’s encouragement, Lebedeva translated Fatma Aliye’s Muslim Women and other works into French. The two women also corresponded directly.

Second, Lebedeva was deeply influenced by Qasim Amin (1863–1908) of Egypt, who published The Liberation of Women in Arabic in 1899, sparking significant discussion. In her work, Lebedeva offered unreserved praise for The Liberation of Women, summarized its key points, and expressed great expectations for Amin as a Muslim male author advocating for the liberation of Muslim women.

Additionally, Syed Ameer Ali (1849–1928), an Indian Muslim who wrote notable English works such as The Spirit of Islam (1891), also had a significant impact on Lebedeva. Indeed, a substantial portion of Lebedeva’s descriptions of historically prominent Muslim women can be traced directly to Ali’s A Short History of the Saracens (1899).

By reading and interpreting Lebedeva’s works, we can gain insights into the spread of Islamic discourse on the equality of men and women, which connected the Russian Empire, the Ottoman Empire, Egypt, and British India.

Lebedeva and Russia’s Practical Oriental Studies

Lebedeva’s proposal to organize a Society of Oriental Studies for the emancipation of Muslim women seemed to be an innovative and original idea. Her vision was to establish branches both inside and outside Russia, involving both men and women, and to maintain neutrality from all religious and political issues while connecting the East and the West through the Society’s activities.

In 1900, ten years after its establishment, the Society was officially recognized by Sergei Witte, the then Minister of Finance. Behind this recognition lay the imperial government’s urgent need to train specialists who could master the languages of the empire’s peripheries and neighboring Near and Far Eastern countries, as well as understand local conditions. This was because neither the Russian Academy of Sciences nor the universities at the time were equipped to provide practical education to meet such needs. The empire therefore required “practical Oriental studies” to facilitate its colonial administration, industrial and commercial development, and international trade and diplomacy.

For Lebedeva, obtaining state endorsement was likely necessary to dispel suspicions of espionage and to make the society a meaningful entity. However, receiving state backing also meant that her original vision of the Society, which was more enlightenment-driven, was subsumed under the empire’s practical demands.

In 1901, Oriental language courses were introduced in St. Petersburg, featuring classes in Turkish, Persian, and Japanese. Rather than focusing on educating Muslim women, Lebedeva became involved in teaching Turkish to future Russian officials. Alongside the official recognition of the Society, Lebedeva was appointed its honorary president, but she reportedly began to distance herself from the organization, taking on a more ceremonial role.

The Society of Oriental Studies later expanded its branches to places such as Tashkent, Bukhara, Askhabad (now Ashgabat, the capital of Turkmenistan), Omsk, Harbin, Khabarovsk, Blagoveshchensk, Odessa, and Tiflis (now Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia). In 1910, it was granted the imperial title by Nicholas II. The Society of Oriental Studies continues to exist today, as the Russian Society of Orientalists. Regrettably, however, Lebedeva’s contributions are seldom mentioned in the history of Russian Oriental studies or the Society.

As Lebedeva’s vision was caught up in the wave of practical Oriental studies, her dream of emancipating Muslim women through the Society of Oriental Studies was left without a clear path forward. After 1912, Lebedeva’s trace is lost; her year and place of death remain unconfirmed, leaving the fate of her life and dreams unknown.

From the perspective of contemporary gender studies and feminist theory, Lebedeva’s arguments are subject to criticism on several points and cannot be idealized uncritically. However, her intriguing, partially forgotten persona as well as her works and network, which spurred the sharing of an Islamic discourse of equality that resonated, are of historical value and merit further exploration. By tracing the fine threads of these connections and delving deeper, what new insights will come to light?

This essay is a restructured version of a presentation that was delivered at the Symposium titled “The Multiplicity of Trade, Borders, and Security” of the National University Institutes and Centers Conference of Section III (Humanities and Social Sciences) held on October 18, 2024.

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「翻訳がつないだイスラーム的男女平等論:

「ロシア初の女性東洋学者」の夢と現実」

(帯谷知可)