Theara Thun (Historian based in Hong Kong)

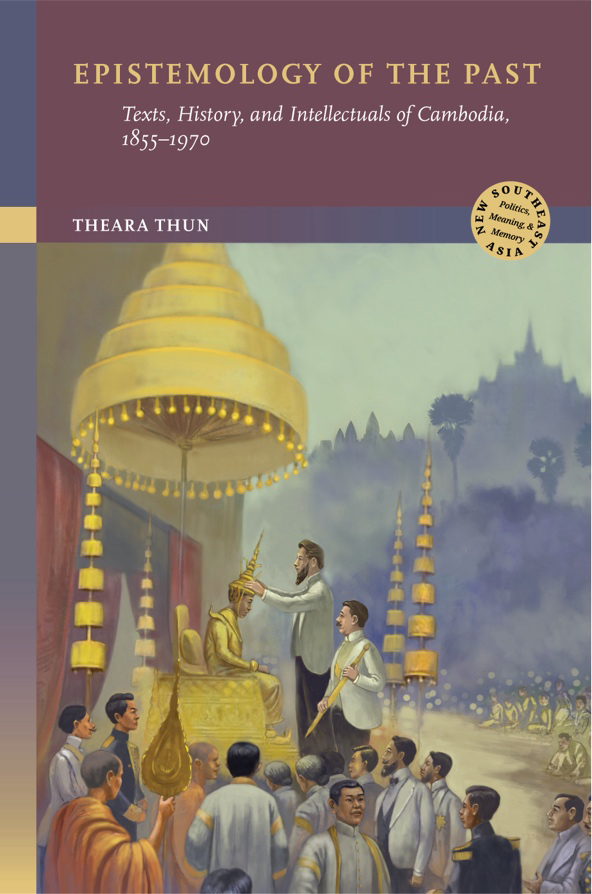

Epistemology of the Past: Texts, History, and Intellectuals of Cambodia, 1855–1970 is based on more than seven years of extensive archival research and writing conducted in Cambodia, Singapore, France, the Netherlands, the USA, Japan, and Hong Kong. It was built upon my award-winning PhD thesis, which was submitted to the National University of Singapore (NUS) under a joint scholarly program between NUS and the Harvard Yenching Institute (Harvard University).

Taking an intellectual historical approach, the book analyzes key historical sources and scholars to critically examine the transition in the historical perception of Cambodia from the precolonial years through the colonial and post-independence eras. It aims to open up avenues for thinking about the transformation of precolonial Southeast Asian intellectual traditions and literary practices, such as chronicle writings. It explores the emergence of new genres of history-making and new ways of historical thinking, which developed within Cambodia’s critical decades of the late 19th and 20th centuries and extended across the broader Southeast Asian region. Simultaneously, the book examines French-Khmer-Thai interactions, the emergence of new communities of scholars, the influential role of state-sponsored institutions, and the expansion of print production.

The book argues that the encounter with colonialism and colonial historiography led Cambodia, and more broadly, Southeast Asia, to experience an epistemological “interface” between the perceptions of the past held in precolonial history-making practices and those of Western-influenced historical scholarship. Throughout the first half of the 20th century and after, new discourses about Cambodian history emerged by drawing on, reconfiguring, combining, or, in some cases, rejecting historical discourses of the 19th-century historical tradition (Thun 2024, pp. 11–12). The new discourses identified elements originating from precolonial indigenous accounts of collective understanding, particularly popular culture, of modern Southeast Asian societies such as Thailand, Cambodia, and Malaysia (see Thun 2024, pp. 124–131; Bernard 2016; Sunait 2000). Given the establishment of modern nation-states across the region, these elements no longer upheld the old mode of historical formulation. Yet, they did not entirely encompass the notions of Western historical writings either. Based on the findings of this book, the Western conception of history never fully displaced premodern indigenous conceptions of the past. Instead, both traditions of historical representation interfaced to create new epistemological categories of historical writing (Thun 2024, p. 11; see also Thun 2020). Thus, by addressing these important yet understudied areas, the book contributes to the understanding of indigenous epistemologies as well as the cross-cultural and intellectual interactions between Southeast Asian societies and the West during the colonial period and beyond.

Restoring local texts, local intellectuals, and local histories

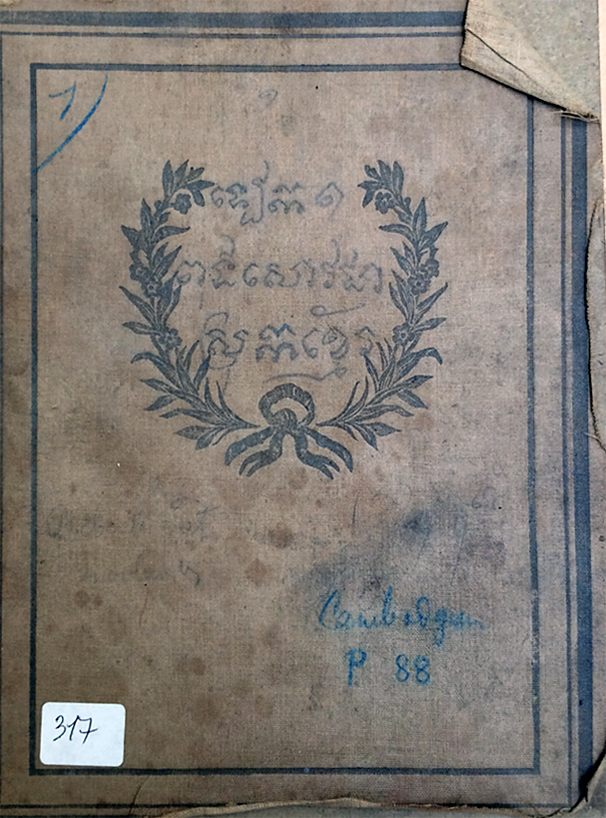

Here, I would like to highlight three restorative aspects of the book. First, given the loss of so many Khmer/Cambodian documents, especially 19th and early 20th century manuscripts and printed texts, due to wars and Khmer Rouge atrocities committed during the 1970s and 1980s, a major intention of this book is to regain these losses. The monograph brings together seventeen original Khmer manuscripts as well as numerous other rare print and microfilm archival materials from libraries and collections in Cambodia and around the world. It exposes these core documents to discussion and scholarly analysis by critically examining their contents and meanings in relation to the broader historical contexts of pre-colonial, colonial, and post-independence Southeast Asia.

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Second, this monograph brings to life key local intellectuals such as Thiounn, Choum Mau, Nhuk-Thèm, and Krasem. In the literature of colonial historiography, French scholars such as Auguste Pavie, Adhémard Leclère, Étienne Aymonier, and Georges Coedés have been widely recognized locally and internationally, given their pioneering contribution to Cambodian and Southeast Asian history. In contrast, the roles and contributions of local figures have hardly been discussed or even mentioned in existing scholarship on the region. Through in-depth examination of local intellectuals’ biographies, the book sheds light on how they harnessed regional and global influences to re-formulate new knowledge that was meaningful to domestic collective values. As one of the very few books that examines regional intellectual history, it discloses the multiple layers and diversities of history-making practices in Southeast Asia, most of which involved local historians, palace astronomers, court officials, monks, teachers, novelists, and translators.

Third, as a Cambodian national who was taught Cambodian history from primary school through university, I have noticed a serious lack of awareness among schoolteachers and university instructors in understanding the unique characteristics of our national history. This knowledge gap arises from a lack of scholarly discussion about the inseparable nature of Cambodia’s national history from the accounts of mythical figures such as the Sweet Cucumber King, which I discuss in the book’s introduction, along with many other fabled rulers. The book’s critical examination of the interface between long-held chronicle writings and colonial historiography has bridged the knowledge gap by discussing how both traditions of historical writing intertwined and evolved in the making of modern Cambodia’s collective history. Therefore, apart from contributing to the scholarship of Southeast Asian studies, the new insights provided in the book can help local schoolteachers, university instructors, and local readers gain a deeper and more critical understanding of their national history.

Photo: Theara Thun, July 2014

Diverse Adaptations

I hope this book will draw the attention of scholars who study encounters between Southeast Asian societies and the West. My discussions of the connections among the Khmer, French, and Thai, especially in chapters 3 and 4 (Thun 2024, pp. 63–109), suggest a complex form of interaction and exchange among local intellectuals. During the colonial period, Western influence over Southeast Asian societies was profound. In Cambodia, French colonialism safeguarded the national border, introduced new laws and government reforms, and appointed new kings and top leaders (as discussed in more detail in Thun and Keo 2024 and Tully 2002). Collaborating with key local rulers and Buddhist leaders, the French also profoundly shaped modern Cambodia’s collective identity, religions, and nationalism (Edwards 2007; Hansen 2007; Harris 2005). However, as for historical writing, throughout the colonial years, Cambodian scholars, including Buddhist monks, never stopped adopting ideas and historical frameworks from Siam/Thailand in their reformulation of Cambodia’s national history. This finding suggests that the making of Cambodia’s modern-day national history, and most likely other components, such as national culture and religion, was hardly the result of adaptation from and collaboration with the French alone (Thun 2024, p. 109 ). On the contrary, it involved a series of adaptations and appropriations of different sources of knowledge originating within the region, the West, and, perhaps, elsewhere.

The book also discusses different “types” of Cambodian scholars, who engaged with both the precolonial history-making tradition and new European archaeological and empirical historical conventions in different ways and to different extents (Thun 2024, pp. 8–9). Although a number of conservatives continued to adapt long-held practices in history-making while selectively incorporating themes and approaches from more recent colonial scholarship, other intellectuals gradually moved away from these practices by engaging with Western-style historical writing. As different scholars competed to advocate their own versions of history, they produced different historical trajectories, which often led to confusions and contradictions in content. What I have concluded in the book is that there was never one single template of collective historical consciousness among indigenous scholars throughout the colonial and postcolonial periods. My conclusion suggests considerable diversity among local scholars in adapting new ideas and scholarship from outside to reproduce shared values and understandings meaningful to their socio-political context(s). Therefore, we should be more cautious when making arguments about the development of new collective identities in the region because there are always different degrees of interpretation towards external influences among local scholars and leaders. Given these differences, the types of new collective identities that they reproduce at the local level are also diverse. We should pay more attention to this diversity, rather than simply labelling them as a new monolithic identity—whether it is Cambodian, Thai, Burmese, or indeed, “Southeast Asian.”

References

Barnard, Timothy P. 2016. “Historiography and Shifting Interpretations of the Death of Sultan Mahmud Syah II.” Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society 89, no. 2: 1–23.

Edwards, Penny. 2007. Cambodge: The Cultivation of a Nation, 1860–1945. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Hansen, Anne. 2007. How to Behave: Buddhism and Modernity in Colonial Cambodia, 1860–1930. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Sunait, Chutintaranond. 2000. “Historical Writings, Historical Novels and Period Movies and Dramas: An Observation Concerning Burma in Thai Perception and Understanding.” Journal of Siam Society 88, nos. 1–2: 53–57.

Thun, Theara. 2020. “An epistemological shift from palace chronicles to scholarly Khmer historiography under French colonial rule.” Journal of Southeast Asian Studies 51, no. 1–2, 132–153.

Thun, Theara. 2024. Epistemology of the Past: Texts, History, and Intellectuals of Cambodia, 1855–1970. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press.

Thun, Theara and Keo Duong. 2024. “Ethnocentrism of Victimhood: Tracing the Discourses of Khmer Ethnicity in Precolonial and Colonial Cambodia.” Asian Studies Review, April, 1–20. doi:10.1080/10357823.2024.2329085.

Tully, John A. 2002. France on the Mekong: A History of the Protectorate in Cambodia, 1863–1953. Lanham, MD: University Press of America.

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「知られざるカンボジアの思想史を解き明かす」(テラ・トゥン)