Minami Tosa (Librarian at CSEAS)

In our daily lives, it is now commonplace to use translation tools and generative AI to understand foreign languages, and it goes without saying that we enjoy the convenience of such tools in various situations. However, when I was a child, I sometimes wondered how much effort people had to go through to understand foreign languages in the days when there was neither the Internet nor dictionaries.

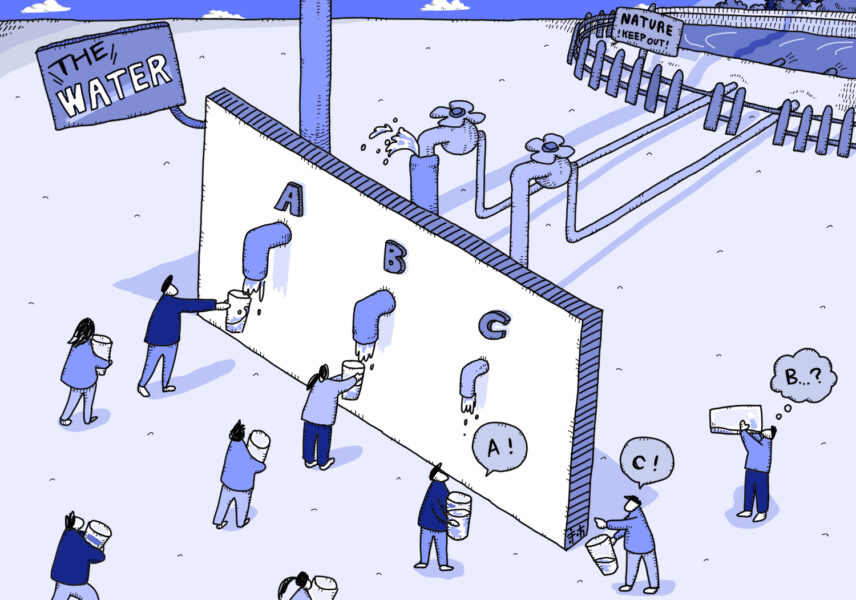

In the book Thoughts on Translation: Shizen and Nature (翻訳の思想:「自然」とNature), Akira Yanabu explores the debate surrounding “自然” (pronounced “shizen”), the standardized translation of “nature” in Japanese. This translation was established in the late Edo and Meiji periods, when numerous translated words were created in response to the influx of Western culture. Does “自然” convey the same meaning as “nature”? The book investigates the different meanings of these two words, and what the gap in their meanings reveals about the ideological differences between Japan and the West.

The book begins with a debate between theater critics Iwamoto Yoshiharu and Mori Ogai, and notes how the two men’s usage of自然clearly holds different meanings. Iwamoto’s 自然 carries the meaning of the word in Japanese before it was used as a translation of the word “nature.” Mori refutes Iwamoto by using the word 自然 as a translation of “nature.” Iwamoto begins by arguing that literature and art are about “depicting nature as it is,” and that the word 自然 encompasses not only beauty and other qualities pursued in literature and art, but also human thoughts and spirits. On the other hand, Mori sees 自然 as a concept in opposition to human activity, convinced that the aesthetic qualities found by humans are not contained in 自然. According to Mori, these qualities are not inherent in nature and are indeed incompatible with nature. Further complicating the matter, Iwamoto gradually became receptive to Mori’s idea and began to incorporate Mori’s sense of 自然. This mixed meaning is not limited to this case but became a nationwide phenomenon as自然 came to reflect the two above-mentioned senses and the influence of the English word “nature” spread. The change of “shizen” in turn influenced modern Japanese intellectual history.

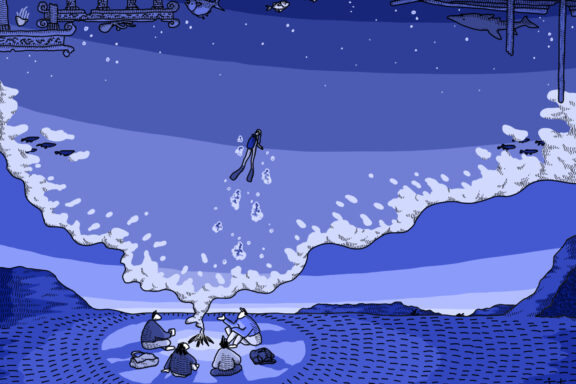

I first read Akira’s book when I was an undergraduate student. At the time, I was interested in the genealogy of environmental protection thought and wanted to learn more about the original meaning of the Japanese word 自然, which appears as a matter of course in the context of nature conservation and environmental issues. Through this book, I learned that translation is not simply a matter of converting one language to another, or one word to another. I began to see that by unraveling the origins, usage, and context of words and their translations, many discoveries can be made.

Furthermore, the task of carefully clarifying the differences between one word and its translation applies not only to the field of language translation, but also to area studies. How should we interpret what we see and hear in the region? What kinds of words should we use to best explain it? The act of deepening understanding and explaining while taking into account the diverse backgrounds and perspectives of the local people (and non-people) is truly a kind of translation work. You may be thinking, “What’s so new about that?” But as I mentioned earlier, as translation tools and AI become commonplace amid our fast-paced lifestyle in a world overflowing with information and words, it is sometimes necessary to return to these basic questions.

Akira Yanabu. 1977. 翻訳の思想:「自然」とNature (Honyaku no Shiso: “自然” to Nature [Thoughts on Translation: Shizen and Nature]). Tokyo: Heibonsha.

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「翻訳という根本的な問いに向けて」

(土佐 美菜実)