Caroline S. Hau (Cultural Studies)

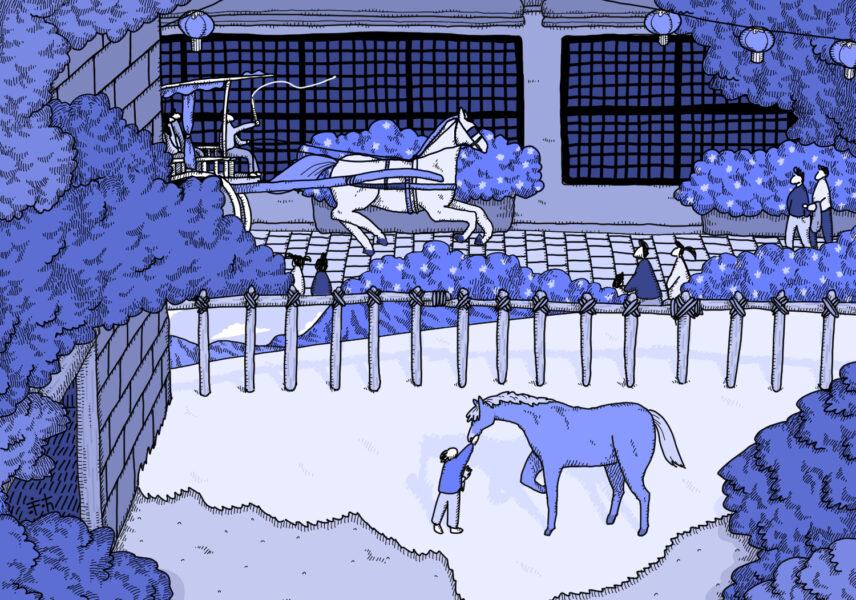

In my childhood during the 1970s, two-wheeled, horse-drawn carriages called kalesas were ubiquitous in Manila’s Chinatown. They brought denizens to and from school, the movie house, restaurant, clinic, store, church, and temple. Their cousin, the spacious karitela, transported goods in bulk from the markets of Santo Cristo and Divisoria. Sporting decorated leather blinkers and trailing clip-clops, clanging brass bells, and dung, horses were as familiar to this urban landscape as people, dogs, and cats.

From their drivers, the kutseros (from the Spanish cochero), I picked up the lingo of the kalesa: to turn right, one used the word mano (from the Spanish for “hand”); to turn left, one said “silya” (Spanish silla, “chair”). In turn, the kutseros communicated with their horses through sounds and gestures—a clucking of the tongue, a swish or pull of the reins, a touch (sadly, at times, a lashing) of the whip, and the horse was off and trotting, galloping or turning a corner, or slowing down and stopping.

Metaphors derived from the olden days when horse and carriage ruled the streets survive in the Filipino language. Buena mano, a customer discount to kick off the workday, originally referred to a coachman who took good care of his horse. Tall tales labeled kuwentong kutsero recall the sight of kutseros chatting among themselves during breaks or idle hours.

Elders exclaimed “Ay, kabayo!” when taken by surprise. Sayings like “Aanhin pa ang damo kung patay na ang kabayo?” (Of what use is grass if the horse is already dead?), “Hampas sa kalabaw, latay sa kabayo” (A blow to the carabao, a welt on the horse, meaning an indirect attack), and “Ti kabálio no bulbuloden, ti ngípenna di kitkitáen” (When a horse is borrowed, don’t look at its teeth) are used to this day.

As cars replace carriages, horses have become an increasingly rare sight in Manila these days, more tourist attraction than daily necessity. Of late, however, I have been reading up on the history of the horse and the impact of the great animal coalition that is “the human-horse dyad” on horse, humanity, biota, and planet.

Proto-horses roamed what is now called the Americas fifty million years ago, but became extinct there during the Ice Age, ten thousand years ago. The domestication 5,500 years ago in the Eurasian steppe of the Equus caballus was a “‘Centaurian Pact’ [that] combined the physical and intellectual power of two creatures into a single cohesive unit. Human beings were both literally and figuratively elevated and empowered by horses.”[1]

For half a million years, Homo sapiens had been “the most significant predator of the horse”.[2] Historians speculate that the first riders of horses may have been children.[3] The earliest trousers were designed to facilitate horseback riding. The Greeks imagined their underworld Hades as a pasture. Horses are mentioned repeatedly in the Rig Veda. Mongolian sacred cairns, called ovoos, are topped with the skulls of horses. Not counting real horses, some 520 terracotta chariot horses and 120 cavalry horses were interred with the first Chinese emperor.

The horse has been food, drink, clothing, labor, means of transportation, vector for pathogens, weapon of war, instrument of power, status symbol, source of comity, messenger, ritual animal, ceremonial prop, prestige good, gift, commodity, employee, pet, companion, and friend.

Greg Bankoff and Sandra Swart argue that the horse was “invented” in the double senses of the horse being “created in the minds of people as a symbol or representational construction” and the horse being “literally morphologically refashioned as a result of anthropogenic intervention”.[4] Horses were, as well, “agents of environmental transformation”.[5]

The steppe has been described as an Asian, inland “sea of grass,” comparable to the Mediterranean in terms of its historical importance and power to connect populations.[6] The horse was arguably one of the main “engines of empire.”[7]

The Chinese quest to acquire “heavenly horses” (大宛馬, as they called the legendary “blood-sweating”[8] Ferghana horses) and improve the quality of their warhorses (戎馬 literally meant “western foreigners’ horses”[9]) was a key issue in Han (206 BCE–220 CE) and Tang (618–907 CE) diplomacy, military strategy, trade, and statecraft. David Chaffetz argues that the horse, rather than silk, was “the true strategic commodity of the time.”[10] Priced at eighteen bolts of silk, a horse cost three times more than a slave girl.[11] Fully ten percent of the Tang state budget was allocated to importing horses.[12] The high value and number of these horses—constituting “the largest component of trade by value on the Silk Road”[13]—provide a compelling case for thinking of the Silk Road as a Horse Road.

Horses arrived in mainland Southeast Asia via Yunnan, China, and their use, particularly in war, spread in the wake of the Mongol invasion during the thirteenth century.[14] They were introduced to the Indonesian archipelago as early as the third century CE, certainly by the ninth century.[15] Horses were among the most valuable commodities of the Portuguese trade empire in Asia, with Goa serving as the port of entry for the horse trade between India and the Middle East.[16]

Javanese horses—which, reflecting the region’s extensive commercial, cultural and religious contacts with the Middle East, were influenced by Persian and Arabian bloodlines—were prized by the Siamese court during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.[17] Horses mainly came to the Philippines with the Spaniards in the second half of the sixteenth century, though Indonesian breeds were already found in south Mindanao.[18]

Colonialism and imperialism played important roles in the global dissemination and creation of horse breeds. Greg Bankoff details Spanish and American attempts at “refreshing the blood” of Philippine native horses—which had adjusted to their environment and diet by becoming smaller—through the import of stallions from abroad. Mirroring colonial thinking about racial mixing, the offspring of the union of “western” male males and “native” female horses were called mestizos.[19] Import of stocks from China and Japan (especially the Nanbu region) filled the growing demand for horses.[20]

Contrary to the World War II propaganda touting Germany’s mechanized military might, Germans, rather than the Soviets, remained heavily reliant on horses for cavalry and logistical support on the Eastern Front. As late as 2001, horses were used in battle against the Taliban by the American Green Berets in Afghanistan.

The framework of human-animal interactions allows us to see our own history, and that of the animals we tend to take for granted, in a new light.

For me, the emotional bond forged in these interactions is evident in the way my father speaks of a mare he had grown up with in Quanzhou, China. My grandfather had acquired her in 1946 for the princely sum of USD100. When my father was eight years old, he was put in charge of caring for her. She was named 虎嘴偏紅 (Tiger Mouth Red Hair) on account of her chestnut color and the white beauty spot on her muzzle.

Noted for her strength and endurance, Tiger Mouth Red Hair had her own room inside the family quarters. After school, my father sat on her back and let her go grazing. Whichever path they took, sometimes across long distances to visit relatives, she always brought them safely home.

My dad was separated from her when, at fourteen years of age, he moved to Hong Kong and the Philippines. Seventy years later, my dad has not forgotten her, nor has he ever forgotten how to ride a horse.

Notes

[1] Timothy Winegard, The Horse: A Galloping History of Humanity (Melbourne: The Text Publishing Company, 2024), p. 2.

[2] William T. Taylor, Hoof Beats: How Horses Shaped Human History (Oakland: University of California Press, 2024), p. 78.

[3] David Chaffetz, Raiders, Rulers, and Traders: The Horse and the Rise of Empires (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 2024), p. 11.

[4] Greg Bankoff and Sandra Swart, “Breeds of Empire and the ‘Invention’ of the Horse,” Breeds of Empire: The ‘Invention’ of the Horse in Southeast Asia and Southern Africa 1500–1950 (Copenhagen: NIAS Press, 2007), p. 10.

[5] Greg Bankoff, “Bestia Incognita: The Horse and Its History in the Philippines 1880–1930,” Anthrozoös (March 2004), p. 4.

[6] Chaffetz 2024, p. 17.

[7] Bankoff and Swart 2007, p. 51.

[8] The hemorrhage was caused by the horse worm Parafilaria multipapillosa.

[9] Chaffetz 2024, p. 84.

[10] Chaffetz 2024, p. 120.

[11] Chaffetz 2024, p. 132.

[12] Chaffetz 2024, p. 120.

[13] Chaffetz 2024, p. 120.

[14] Bankoff and Swart 2007, p. 11.

[15] Peter Boomgard, “Horse Breeding, Long-Distance Trading, and Royal Courts in Indonesian History, 1500–1900,” in Bankoff and Swart 2007, p. 35.

[16] Ralph Kauz, “Horse Exports from the Persian Gulf Until the Arrival of the Portuguese,” Pferde in Asien: Geschichte, Handel und Kultur [Horses in Asia: History, Trade and Culture], edited by Bert G. Fragner, Ralph Kauz, Roderich Ptok, Angela Schottenhammel (Wien: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften, 2009), pp. 129–36.

[17] Dhiravat na Pombejra, “Javanese Horses for the Court of Ayutthaya,” in Bankoff and Swart 2007, pp. 65–81.

[18] Bankoff and Swart 2007, p. 13.

[19] Bankoff 2004, p. 13.

[20] Bankoff 2004, p. 9.

(Illustration: Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「馬の力」(カロライン・ハウ)