Hiroshi Ishii (Maritime archaeology, Modern conflict archaeology)

The first time I heard the term “Underwater Archaeology” was in the middle of a desert. During a field school in the high desert of Oregon, I excavated caves and was covered in sand every day. One evening, as we sat around a campfire to ward off the chill after sunset, a PhD candidate casually mentioned the work of “underwater archaeologists” while sipping a craft beer. It struck me as something surreal and mysterious, and left a lasting impression. At the time, however, I had no way of knowing that this subdiscipline of archaeology would one day steer the course of my life.

Growing up in a fishing town in the Shonan area of Kanagawa, the sea has always been close to my heart. For Japanese people who live in an island nation, the sea symbolizes both a barrier to the outside world and a connection to it. There is no shortage of transformative innovations that have crossed the ocean when we look back through Japanese history, such as rice farming, Buddhism, firearms, and modern industrialization. But while I was living in Japan, I never encountered the term “Underwater Archaeology.” It was only later, after crossing the Pacific Ocean for my studies in the United States, that I repeatedly came across it. It gave me a new perspective on my motherland.

Underwater archaeology, which has evolved alongside advances in underwater exploration technology and the widespread adoption of scuba diving, is one of the most cutting-edge fields in archaeology and is expected to continue growing globally. Considering the total length of Japan’s coastline and the vastness of its maritime territory, it is easy to imagine the immense potential for archaeological discoveries that lie beneath the surface of Japanese waters. However, despite being one of the world’s leading maritime nations, Japan’s public awareness of underwater archaeology remains relatively low. In this context, Dr. Randy Sasaki’s Maritime Archaeology: Frontier at the Global End is a welcome introduction to the field of underwater archaeology and its alluring appeal.

Dr. Sasaki, a nautical archaeologist, not only introduces underwater archaeological sites and their histories in both Japan and around the world, but also explains the technologies used in underwater exploration. Blending personal stories, including experiences studying in the United States and first encounters with underwater archaeology, with humor, the book provides a friendly and engaging read in an accessible manner. Although the latter part of the book feels somewhat rushed due to space constraints—an understandable result of the author’s overflowing passion for the field—it nonetheless serves as an excellent introductory guide.

In his book, the author argues that the term “Underwater Archaeology” is not ideal. Although we refer to ourselves as underwater archaeologists, we are ultimately archaeologists at heart and should be defined by our research subjects, not by the environments in which we work. It is just that the objects of our study—whether ships, trade goods, or submerged landscapes—tend to be found underwater. Overcoming the unique underwater environment, sometimes even utilizing it, we explore the traces of human history. Due to the specialized nature of the work, an underwater archaeologist sometimes must jump from site to site, much like a traveling troubadour. Despite such hardships, Dr. Sasaki passionately focuses on the appeal of underwater archaeology, dreaming of a day when underwater archaeologists and underwater heritage sites will be commonplace in Japan.

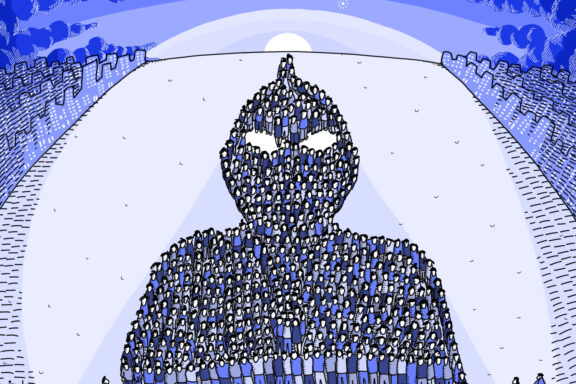

(Illustration: Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「水中考古学の可能性」(石井 周)