Julie Ann de los Reyes (Geography, Political Ecology)

My home country, the Philippines, is no stranger to storms. Each year, an average of 20 tropical cyclones sweep across the archipelago, a fact so routine that typhoons have become part of the rhythm of life—anticipated, endured, and, with luck, survived. But in September 2009, Typhoon Ondoy (internationally known as Ketsana) struck with a force and fury that unsettled even the most storm-hardened residents. In just a few hours, it unleashed a month’s worth of rain over Metro Manila, submerging vast swathes of the capital in floodwaters.

Kristian Saguin’s Urban Ecologies on the Edge opens with this now familiar story: a powerful storm, vulnerable communities, overwhelmed infrastructure—the first of several intense typhoons that would expose the fragility of Metro Manila’s urbanisation. Many Filipinos will remember the roads turning into rivers, the cars stacked on top of each other like toys, and families huddled on rooftops awaiting rescue.

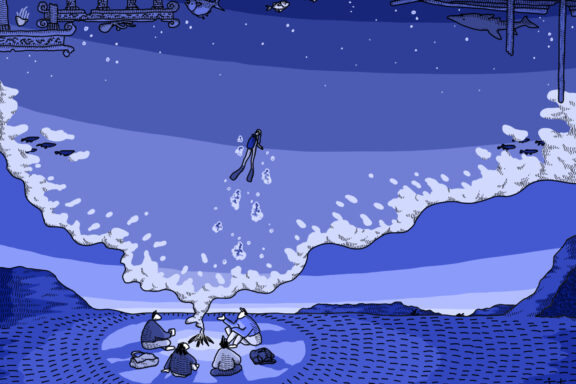

But Saguin’s account extends beyond the city’s margins—both literally and conceptually. Drawing our attention to Laguna Lake, the country’s largest inland body of water located on Manila’s southeastern fringe, Saguin shows how it plays a central role in the city’s flood control measures by absorbing runoff from its rivers and canals. Keeping the city dry, he notes, requires the deliberate redirection of excess water toward the lake, transferring floodwater risks onto communities living along the lake’s shores.

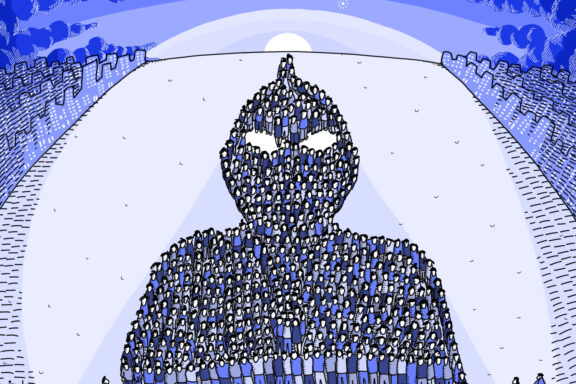

Urban Ecologies on the Edge invites us to see stories we think we already know in entirely new ways. Cities are often seen as core sites of innovation, economic growth, and progress, obscuring processes that sustain urban life—processes that often lie beyond its visible geographical and administrative boundaries. The book reminds us that the everyday functioning of cities like Manila depends on the flows, labour, and ecologies that operate “on the edge.”

Laguna Lake’s design and evolution are shown to have been closely tied to the needs and vulnerabilities of the capital. Aside from functioning as a sink for “undesirable hazards” like stormwater, it has also been imagined and reimagined as a “convenient frontier” for urban food production, water supply and land reclamation. The lake is a major site for the cultivation of commercially important species such as tilapia, milkfish (bangus), and carp, which are staples in the Filipino diet and widely consumed in Metro Manila. Aquaculture fish production in the lake, which increasingly overtook traditional capture fisheries, is intended to help meet the food demands of the growing metropolis, offering a readily accessible source of protein.

The resource flows enabled by the lake have quietly underpinned the growth of the capital, from the postwar years of rapid urban expansion in the 1950s and 1960s to the present-day megacity of over 13 million people. A long history of technological, political and economic interventions in the lake, framed as necessary for progress or protection, has continuously reshaped its development and its role in relation to the city. But it is not just a passive space: state planning, capitalist ventures, intransigent nature, and everyday practices of marginalised actors collide—often in messy, improvised, and unexpected ways—producing a contested landscape where the demands of urban survival are negotiated. It is a crucial arena where the struggles over risk, resources, and belonging are actively unfolding.

Despite Laguna Lake being rendered invisible, if not outright expendable, in dominant narratives of urban development, the book powerfully argues that it is, in fact, central to city making. As Metro Manila’s “toilet and fishbowl” (in Saguin’s words), the lake occupies a paradoxical position as both dumping ground and life source, absorbing the undesirable while providing the essential. This dual role is not incidental but foundational to the city’s survival. Laguna Lake, in this regard, is not only shaped by the city; it actively shapes it in turn. It challenges us to look beyond the immediate spectacle of crisis that typhoons like Ondoy unleash—and ask harder questions about the dynamics that produce urban vulnerability and resilience—and who bears the cost in the process.

(Illustration: Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「周縁にて」(ジュリー・アン・デロスレイエス)