Mario Lopez (Anthropology)

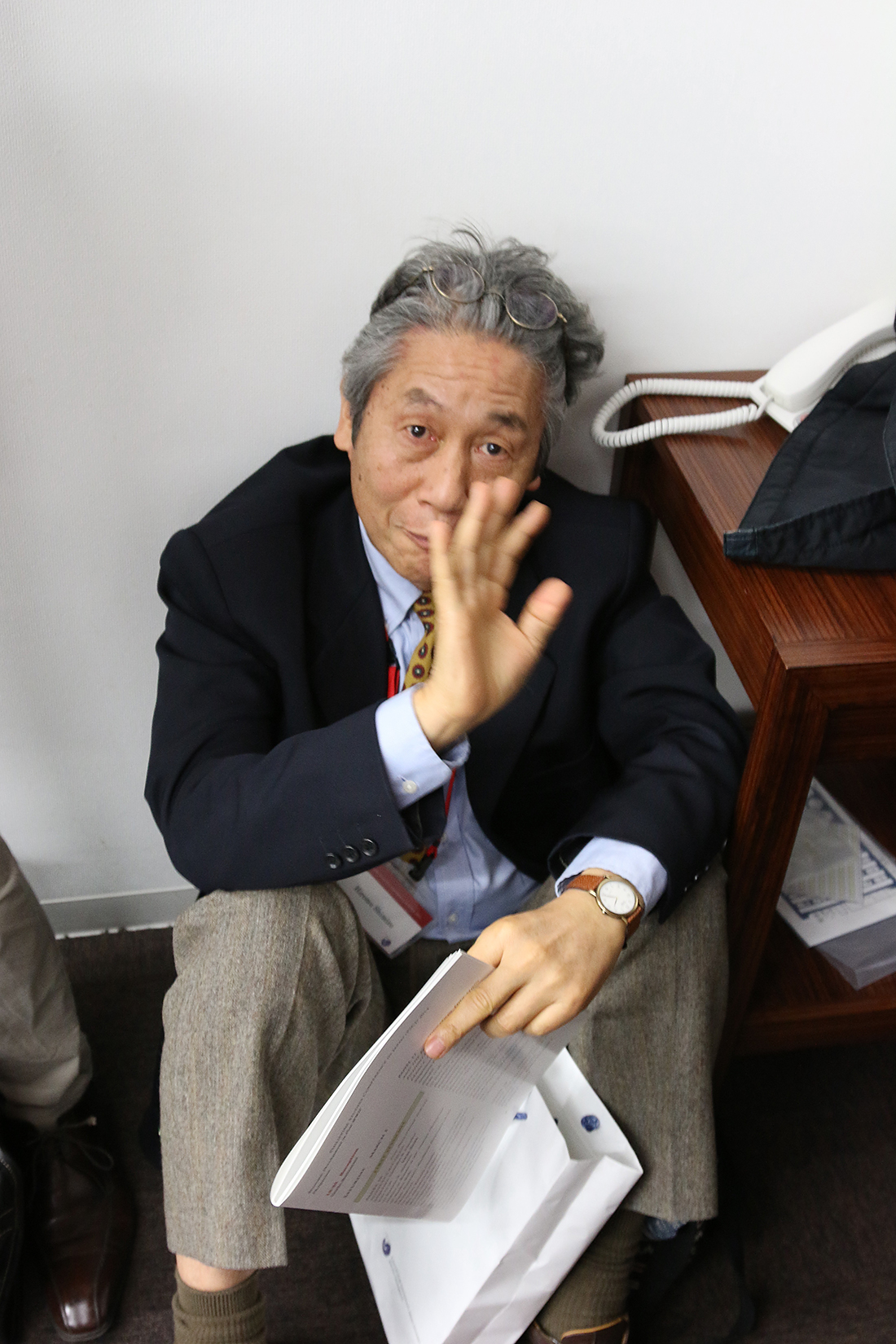

On February 22, 2025, Emeritus Professor Shimizu Hiromu passed away. An anthropologist and eminent expert on the Philippines, he was affectionately known as ‘Hiro’ to his friends. Over the years he devoted himself to the education and mentoring of students, and his contributions have been widely recognized both within and beyond academic circles. Throughout a distinguished career, he authored a total of eight monographs—five in Japanese and three in English—and published over 70 articles in both languages. After completing his graduate studies at the University of Tokyo, he served there as an Assistant Professor, later advancing to professorships at the Graduate School of Social and Cultural Studies Kyushu University (1985–2006), and ultimately the Center for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS) Kyoto University (2007–2017) where he was actively engaged in both research and education.

Born in Yokosuka City, Kanagawa Prefecture in the aftermath of World War II, Professor Shimizu Hiromu grew up under the imposing presence of the United States Navy which was stationed there during the postwar period. The formative experience of living under the shadow of the armed forces sparked a deep interest in the global structures of power and influence on popular culture in contemporary Japanese society. It also set in motion a deeply personal and intellectual starting point for his anthropological voyage—as a means to “unlearn” and critically examine the pervasive influence that the U.S. had exerted in shaping postwar Japan.

In 1976, as a young doctoral student, he began living among the Aeta people, an indigenous people who live in the mountainous regions of Luzon in the Philippines—a community he would remain engaged with over four decades. Under the mentorship of the renowned anthropologist Chie Nakane, he conducted extensive fieldwork that resulted in his first two major works, Pinatubo Aytas: Continuity and Change (1989) and Dekigoto no minzokushi: Firipin Negurīto shakai no henka to jizoku (An Ethnography of Events: Change and Continuity in Philippine Negrito Society, 1990). These studies were highly acclaimed for their detailed exploration of Aeta history and for portraying the dynamism of their social life and their remarkable adaptability to environmental and societal change.

Within Japanese academia, he gained recognition for his groundbreaking analysis of the 1986 Edsa Revolution. His third book, Bunka no naka no seiji: Firipin “Nigatsu kakumei” no monogatari (Politics within Culture: Narratives on the Philippines’s People Power Revolution, 1991) explored the background of the popular uprising against the Marcos dictatorship. This ethnography examined the pivotal role of the Catholic Church and the profound religious undertones that influenced the course of the revolution. This work represented an attempt to understand the inner spiritual world of political activists and ordinary citizens, challenging conventional interpretations that framed political processes as struggles and compromises between politicians and parties. He offered a fresh perspective—one that highlighted how cultural and religious narratives shaped political movements, reexamining the foundations of the “people’s power” revolution beyond traditional analytical frameworks.

In June 1991, Mount Pinatubo erupted in a massive volcanic explosion severely affecting one of his primary field sites. The indigenous Aeta who lived in the surrounding areas were forced to evacuate, suffering incredible loss and upheaval. At the time, Professor Shimizu was on sabbatical, but the disaster compelled him to step beyond the traditional boundaries of academic research. For nine months, he worked as a volunteer with a non-governmental organization (NGO) providing emergency relief and reconstruction assistance. These experiences deeply shaped his future career prompting him to reconsider the social responsibility of researchers. In other words, he began to question the conventional role of the anthropologist as a passive observer—an assumption long taken for granted—and gradually shifted toward a more engaged participatory approach. This shift was vividly reflected in his fourth and fifth books, The Orphans of Pinatubo (2001) and Funka no kodama: Pinatubo Aeta no hisai to shinsei wo meguru bunka, kaihatsu, NGO (Echoes of the Eruption: Culture, Development, and NGOs among the Pinatubo Aeta, 2003). These works documented firsthand accounts of the eruption and provide a detailed portrayal of how Aeta society was transformed through displacement and resettlement, and how they adapted to new ways of life. These works represented both an anthropological turning point and a practice-oriented approach that urged fellow anthropologists to confront the lived realities of people who face profound adversities.

His deep commitment to the Aeta and Philippine Studies was also evident in the order of his publications. His first Pinatubo Aytas (1989) and his fourth The Orphans of Pinatubo (2001) were both written in English and published first in the Philippines—ensuring they would reach their intended audiences. Notably, the latter was published not only in English, but also as a bilingual edition in both English and Filipino. This deliberate choice underscored his strong belief that research should not remain confined to academic discourse but also be accessible to the communities studied.

Over the course of his long-term engagement with Philippine society, he also expanded the scope of his fieldwork to Hapao, a remote village located in the mountainous region of Ifugao Province in Northern Luzon where he conducted research over a 16-year period. This culminated in his sixth book, Kusanone gurōbarizēshon: Sekai isan tanadamura no bunka jissen to seikatsu senryaku (Grassroots Globalization: Cultural Practice and Livelihood Strategies in a UNESCO World Heritage Terrace Village, 2013) which examined how globalization unfolds in a village inscribed on the World Heritage list. The ethnography explores a range of local initiatives, including villagers’ reforestation initiatives, a cultural revival movement and the artistic contributions of the celebrated Filipino Filmmaker, Kidlat Tahimik. Through exploring these, he offered insights into how people on the peripheries of globalization absorb, adapt, and repurpose global influences in ways that sustain and enrich their own lives. And it was through this work that he proposed the concept of an “anthropology of response-ability” (Ōtō suru Jinruigaku): a call to cultivate a deeper sense of responsibility toward the communities they engage with. Recognizing the importance of bringing this perspective to a broader international audience, he revised and had the book translated into English, publishing it in 2019, under the title Grassroots Globalization: Reforestation and Cultural Revitalization in the Philippine Cordilleras. This reinforced his commitment to cross-cultural dialogue and marked an important contribution to global academic discussions on globalization, cultural sustainability, and the anthropology of morality and ethics.

His final work, Aeta, hai no naka no mirai: Daifunka to sōzōteki fukkō no shashin minzokushi (The Future of the Ayta amidst the Ashes: A Photo Ethnography of Volcanic Eruption and Creative Reconstruction, 2024) is the culmination of his nearly 50-years of engagement with the Aeta. It is a rich visual tapestry that weaves together images and narratives for both academic and general audiences. The book traces the lives of the Aeta before and after the catastrophic 1991 eruption of Mount Pinatubo and highlights the remarkable resilience of the Aeta. It underscores the vital role anthropologists can play in what he called the “slow work” of anthropology in post-disaster community rehabilitation. Rather than emphasize short-term interventions, he advocated for sustainable, long-term approaches to rebuilding communities. A recurring theme in this work and previous ones is the idea of “Sōzōteki fukkō (creative reconstruction),” (Shimizu et al. 2020). While devastating, natural disasters can also serve as catalysts for transformation, renewal and positive change, both for individuals and communities alike. This perspective—one that balances sensitivity to suffering with a hopeful vision of cultural regeneration—resided at the heart of his research and practice.

A deeply humanistic scholar, he intensely approached community transformation through a deep commitment to fieldwork. His extensive time in the field not only shaped his understanding of anthropology but also helped him contextualize his own personal journey. These experiences became the foundation for a vision he held for the discipline’s future. Reflecting on this approach he described it as a “radical path of participatory activity, a most extreme yet fundamental form of participant observation” which became the cornerstone of his fieldwork (Shimizu 2017, 20). This radical commitment to participation became the core of his approach. He challenged the conventional notion of the anthropologist as a passive observer, instead emphasizing the importance of meaningful action and advocating for a redefinition of anthropology itself. For him, anthropology was not merely an intellectual exercise—it was a discipline deeply rooted in the struggles and everyday lives of the people it seeks to understand. Throughout his life he strongly advocated for expanding participatory activities and called for deeper engagement and expanded participation. He continuously urged the discipline toward a more collaborative, ethically grounded and socially committed practice.

Professor Shimizu was also the recipient of numerous awards. In 1991, his second book was awarded the prestigious Shibusawa Prize from the Shibusawa Foundation for the Promotion of Ethnology and in 2016, he received the Japanese Society of Cultural Anthropology Award for his 2013 ethnography Grassroots Globalization. In 2017, the same work was further honoured with the Japan Academy Prize. Most recently, in 2024, he was honoured with the Order of the Sacred Treasure Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon in recognition of his outstanding contributions to academia.

In 2006, he transferred from Kyushu University and joined the Centre for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS). He had hoped that his new position would allow him more time to immerse himself in fieldwork at a slower, more reflective pace. However, that hope was short-lived, as he was appointed Director from 2010–2014. During his tenure he played a pivotal role in helping establish the Consortium for Southeast Asian Studies (SEASIA) and helped found the English language Journal Southeast Asian Studies. These initiatives were instrumental in elevating CSEAS to a globally recognized hub for research of Southeast Asia, and they remain among his most significant institutional achievements. Though his administrative duties limited the time he could spend in the field, he channelled his energy toward strengthening international networks and academic exchanges. In doing so, his legacy extended beyond the realm of hands-on fieldwork, leaving a lasting impact on the institutional and organizational structures that support area studies today.

As a former student and later as a colleague, above all, what I remember most fondly is his role as an educator. Over the many years he dedicated himself to teaching, he offered persistent support and generous guidance to countless graduate students. I vividly recall him one evening, beer in hand, beaming with pride to blurt out “All my students have jobs now; I struck home runs with all of you!” Such moments were filled with a deep affection for his students and a quiet, unwavering confidence in his calling as a teacher. Among other memorable moments I have during his time at Kyushu University, his late-night doctoral seminars stand out. They would frequently spill out into a local Izakaya (Japanese pub) where discussions continued late into the evening. It was there that we learned from him what “real participant observation” meant—not just as a research method, but as a way of connecting with others over shared drinks and conversation. He showed us the importance—and the joy—of engaging with people in an open, humanistic way. Even after retiring from CSEAS, his passion for education did not wane. He continued to share the same energy and commitment as a Specially Appointed Professor at Kansai University’s Faculty of Policy Studies. His influence extended far beyond the walls of any single classroom, continuing to inspire generations of students.

His sharp intellect and analytical rigor—paired with a sense of humour that often came across as self-deprecating, yet in truth was rooted in a deep appreciation for ambiguity and complexity—remains vividly etched in my memory. He possessed a rare ability to recognize the multilayered, often contradictory nature of things, and exactly because of that, he could laugh at all forms of authority, including his own. In countless moments, he could weave together both wit and insight, sharing stories full of warmth that brought laughter and reflection. And I also remember those quiet Saturday afternoons, when he would hunker down in his office working on a manuscript with the sound of the Rolling Stones or the Beatles drifting out into the hallway. The music and those melodies come back as a sound that evokes both comfort and a sense of loss.

He often insinuated he was “betwixt and between,” neither here nor there, suspended in the in-between. Yet it was precisely with that stance that his true strength lay: the ability to build bridges across cultures, ideas, and people. Though his passing brings a deep sense of loss, the connections he nurtured and the lives he touched continue to carry his spirit forward. And it is in those relationships and encounters, that his presence endures.

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my gratitude to Professor Yoko Hayami, Inspector General for the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS), Professor Kusaka Wataru at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies and Mr. Testsuya Suzuki, Former Editor-in-Chief, Kyoto University Press and for their valuable advice in writing this.

References

Shimizu, Hiromu 清水展. 1990. Dekigoto no minzokushi: Firipin Negurīto shakai no henka to jizoku 出来事の民族誌:フィリピン・ネグリート社会の変化と持続 (An Ethnography of Events: Change and Continuity in Philippine Negrito Society). Fukuoka: Kyushu University Press.

───. 1991. Bunka no naka no seiji: Firipin “Nigatsu kakumei” no monogatari 文化のなかの政治:フィリピン「二月革命」の物語 (Politics Within Culture: Narratives on the Philippines’s People Power Revolution). Tokyo: Kōbundō Publishing.

───. 2003. Funka no kodama: Pinatubo Aeta no hisai to shinsei wo meguru bunka, kaihatsu, NGO 噴火のこだま:ピナトゥポ・アエタの被災と新生をめぐる文化・開発・NGO (Echoes of the Eruption: Culture, Development and NGOs dealing with the Disaster and Regeneration of Pinatubo Aeta). Fukuoka: Kyushu University Press.

───. 2013. Kusanone grōbarizēshon: Sekai isan tanadamura no bunka jissen to seikatsu senryaku 草の根グローバリゼーション:世界遺産棚田村の文化実践と生活戦略 (Grassroots Globalization: Reforestation and Cultural Revitalization in the Philippine Cordilleras). Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

───. 2024. Aeta, hai no naka no mirai: Daifunka to sōzōteki fukko no shashin minzokushi アエタ 灰のなかの未来:大噴火と創造的復興の写真民族誌 (The Future of the Ayta amidst the Ashes: A Photo Ethnography of Volcanic Eruption and Creative Reconstruction). Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

───. 2016. Reflections on the “Anthropology of ‘Response-ability’ through Engagement: A Long and Winding Road from Field Work to Ethnography, Commitment, and Beyond. Japanese Review of Cultural Anthropology, Vol 18(1): 5–36.

Shimizu, Hiromu. 1989. Pinatubo Aytas: Continuity and Change. Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press.

───. 2001. The Orphans of Pinatubo: Ayta Struggle for Existence. Manila: Solidaridad Publishing House.

───. 2019. Grassroots Globalization: Reforestation and Cultural Revitalization in the Philippine Cordilleras. Kyoto: Kyoto University Press and Transpacific Press.

Shimizu, Hiromu and Iijima, Shuji (Eds.) 清水展・飯嶋秀治編著. 2020. Jimae no shisō: Jidai to shakai ni ōtō suru fīrudo wāku 自前の思想:時代と社会に応答するフィールドワーク (Homegrown Thought: Fieldwork in Response to Society and Its Times). Kyoto: Kyoto University Press.

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「周縁に立ち、出会いを紡ぐ人類学者:清水展教授を偲ぶ」

(マリオ・ロペズ)