Kisho Tsuchiya (Southeast Asian Studies, Modern History)

In May 2025, Cold War Asia: Unlearning Narratives, Making New Histories, edited by Masuda Hajimu (associate professor, Department of History, National University of Singapore), was published by the University of North Carolina Press. The volume emerged from a far-reaching international collaborative research initiative based at the National University of Singapore (NUS), titled Reconceptualizing the Cold War: On-the-ground Experience in Asia. An introductory essay by Masuda (2025) offers an overview of the book’s aims, while elsewhere I have written a report on the project’s initial workshops (Tsuchiya 2019). Alongside these contributions, I would like to offer the following reflections—drawn from my perspective as a former teaching assistant, graduate student, and project manager of Masuda’s—on his intellectual persona and the collective journey we undertook in Singapore.

Encounter at NUS: “Conflict in History, History in Conflict”

In the final months of my MA in Southeast Asian Studies at NUS in 2012, I found myself at a crossroads. It was then that Professor Reynaldo Ileto—a pioneering historian of the Philippines, who was set to retire that year—offered me advice that would alter my path: “You will make a good historian because you are good at philosophy and are enthusiastic about critical thinking. Rather than becoming a UN bureaucrat, your personality might be better suited to an academic career—writing what you want to write.”

Buoyed by his words, I requested Maitrii Aung-Thwin (I liked his professional and deconstructive theoretical orientations) to be my main supervisor and entered the PhD program in History in August 2013. Around that time, I found out that Oliver Wolters (the historian who had been Ileto’s PhD thesis advisor) altered Ileto’s career path away from engineering by saying that he would make a “decent historian” because he was good at mathematics (Ileto 2002). I laughed a lot when I realized how Professor Ileto used the same trick on me.

When I entered the program, the head of the history department told me, “You’re Japanese, right? If you want to survive in this field, you’ll need to be able to teach your country’s history. So, I’m assigning you to assist Hajimu Masuda. He’s also Japanese—and in ten years, he’ll be a superstar in academia.”

That was the first time I heard Masuda’s name. A former journalist with Mainichi Shimbun, he had completed a PhD in history at Cornell. At the time, he was in his second year at NUS, still an assistant professor, and little known in wider academic circles. I was assigned as his teaching assistant for a course titled Modern Japanese History: Conflict in History, History in Conflict. The course themes, such as “the Cold War among the people” and “social warfare” signaled a perspective that would eventually come to define what Masuda termed Cold War Asia. His lectures brought into view the tensions and upheavals that unfolded within societies across the ages: from the Rice Riots and the turmoil of the Bakumatsu era, to the wartime expansion—and postwar retrenchment—of women’s roles, to the ambiguous hopes and insecurities embedded in the “freeter” phenomenon (フリーター現象) after Japan’s bubble years. This was not the boring chronology of events or the burdensome memorization of kanji names of historical figures that I had known in school. The course gave voice to people’s aspirations, anxieties, resentments, fears, and quiet rebellions—tracing the emotional undercurrents of history. The stories of Japanese people of the past felt alive, and teaching alongside Masuda was the first time I found genuine joy in a Japanese history class.

The Shock of Cold War Crucible

It was not until 2015, while auditing Masuda’s graduate seminar, Reconsidering the Cold War, that I fully grasped what the department chair meant by telling me, “He’ll be a superstar in academia.” Graduate courses at NUS’s department of history were famously rigorous: each week, students were tasked with reading an entire scholarly monograph in English (which was not the first language of many) and writing a critical review. Taking just two or three courses per semester could mean tackling 30 to 45 books.

That semester’s reading list included seminal works that have shaped Cold War Studies since the 1990s: John Lewis Gaddis’s authoritative narrative of the Cold War; Jeremi Suri’s portrayal of détente as an instrument of government control of resistance; Odd Arne Westad’s sweeping account of The Global Cold War; and Heonik Kwon’s The Other Cold War, which was grounded in lived experiences from Korea and Vietnam (Gaddis 1998; Suri 2005; Westad 2005; Kwon 2010). Despite their innovations in Cold War Studies, these influential works shared a common assumption: the Cold War was driven by U.S.–Soviet rivalry, with social movements, “hot wars,” and the Global South either subplots or extensions of that rivalry.

During the semester in which I audited his graduate course, Masuda’s first monograph, Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World, was published. I still remember the jolt I felt reading it for the first time. The book dismantled the dominant narrative of an East–West divide that was the premise of all the texts we had engaged with and presented an altogether different view, one in which the Cold War’s logic was reproduced from the ground up, across both blocs.

The question that lingered in my mind was simple yet overwhelming: “How did he write this book?” It drew on an enormous array of sources and captured the voices of ordinary people across the world, all in prose that undergraduates could understand. I had met many brilliant thinkers at NUS, but reading Cold War Crucible generated a sensation I had rarely experienced: a mix of awe, excitement, and a bit of despair. “Can I ever produce something of this scale after many years of dedication? Honestly, I don’t think so.” That is what I felt.

In 2015, studies of the Cold War still largely orbited around questions like “Who started it?” and “Who is to blame?” Few questioned these frames. But Masuda asked something more radical: “What exactly was the Cold War?” Drawing from over fifty archives across the world, he argued that the Cold War was “an imagined reality”—a political fantasy that proved useful to many, and therefore, continued to be reenacted, again and again. His unorthodox framing unsettled many senior historians. Among graduate students, reactions ranged widely. Some clung to traditional frameworks; others were puzzled. But some—me included—felt electrified, as if witnessing the birth of a new paradigm, the beginning of a new age of Cold War Studies. That feeling convinced me that I had much more to learn from Masuda. I requested that he become one of my supervisors for my PhD dissertation on the global production of knowledge about (East) Timor, and later I became a postdoctoral fellow on the Reconceptualizing the Cold War project (Tsuchiya 2024).

The Collaborative Research Project

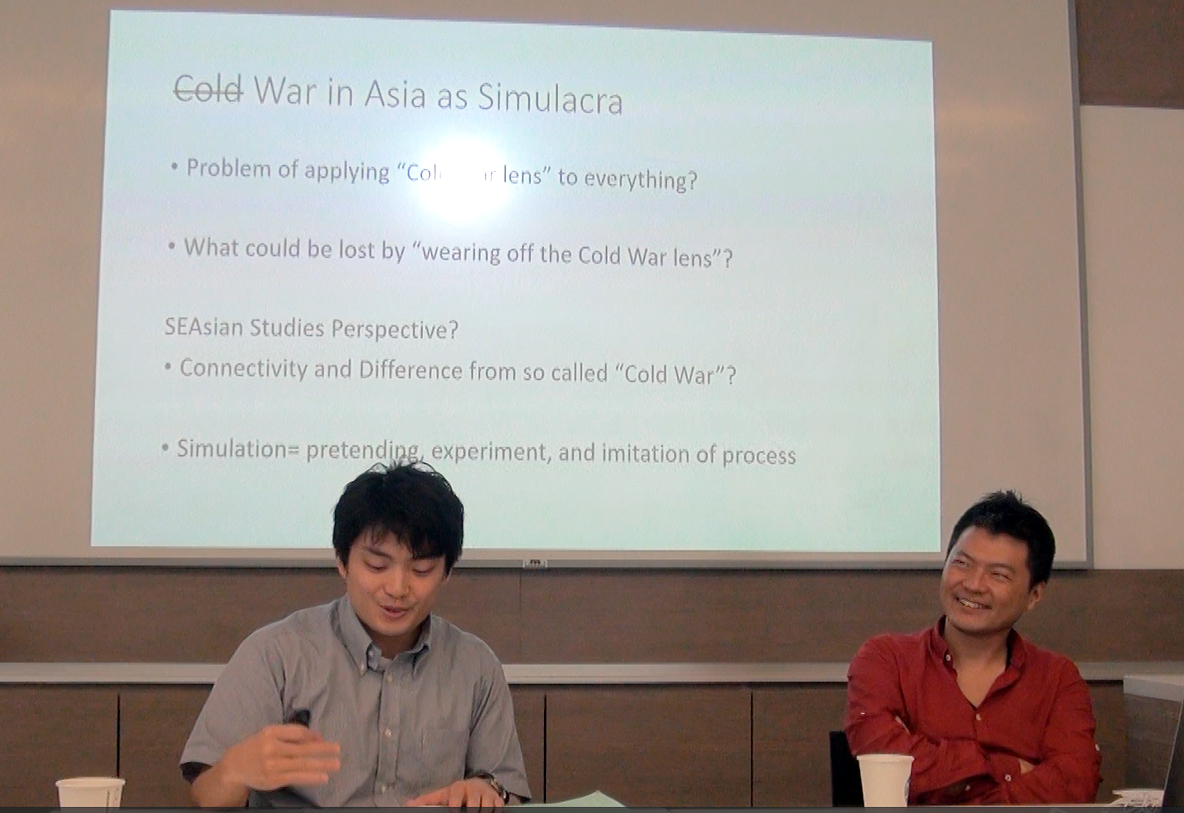

The Reconceptualizing the Cold War project, part of whose contributions came out as the edited volume Cold War Asia, originated from a simple yet radical question posed by Masuda: “What exactly was the Cold War for ordinary people in Asia?” This question—approached inductively through oral histories collected across the region—formed the backbone of the multi-year, multi-sited research effort.

However, not all the 80-plus researchers involved in the project initially shared Masuda’s interpretive lens. As a result, the volume offers a vibrant spectrum of perspectives on how the so-called “Cold War” was lived and perceived on the ground. Our discussions were characterized by a diversity of views on what constitutes the essence of the “Cold War,” which ranged from international tensions filtered through the lens of superpower rivalry; localized reinterpretations of capitalist and communist ideologies; a strategic borrowing of rhetoric to address grassroots concerns; to what I have described in my chapter as “many wars imagined as one.”

Masuda challenges the dominant historiographical habit of treating “the Cold War as weather”—as an inevitable global condition, ambient and omnipresent. Against this backdrop, he advances a provocative counterargument that ordinary people, by continually invoking and adapting Cold War logic, exercised agency in shaping their social (and ultimately international) realities. This notion contrasts with critiques offered by researchers focusing on state violence, such as the Indonesian military’s mass killings of “communists” in 1965 or the devastation wrought by U.S. airstrikes in Laos and Vietnam. Some of these scholars argue that the Cold War was, in effect, a weather system imposed from above: the byproduct of elite decisions, bearing down on populations who had little say in the matter. Their work resonates with ongoing human rights discourses, which emphasize structural violence and the imperative to hold powerholders accountable.

Despite the range of views, the project continued to emphasize a shared conviction: that power is never only about those who wield it. Rather, it is sustained—sometimes unwittingly—by the complicity, fear, hope, or silence of the many. The Reconceptualizing the Cold War project insisted that to fully understand the “Cold War,” we must examine not only state leaders but also ordinary supporters and dissidents. To this end, each chapter in Cold War Asia attempts to recover the textures of ordinary life: to take seriously the possibility that everyday people in Asia were not only victims of the Cold War but at times its agents, intermediaries, and accelerants.

This orientation may also reflect a biographical discontent—one that Masuda and I, as Japanese scholars, have shared. Beneath our investigations lies an unresolved question: Was it not the general public—the ordinary people who cheered on the militarist state, who became soldiers, or sent their loved ones off to war—that propelled Japan into the disaster of World War II? Masuda will publish another book in Japanese to answer this question by September this year.

It is with such historical sensitivity that Masuda continues to challenge scholars and students in area studies with questions such as: “How can area specialists confront and subvert dominant master narratives by offering alternative historical narratives?” Masuda calls us to think about how we might dismantle the entrenched division of labor in global scholarship, wherein world and global historians dictate the overarching frameworks, while area studies scholars are relegated to documenting local impacts. In this light, the Reconceptualizing the Cold War project was not merely an effort to “add in” Asian voices to an already crowded Cold War historiography. It was, fundamentally, a global history project with Asia as Method and a bottom-up approach: One that sought to foreground fragmented field-site accounts to build new global histories. It invited area studies scholars and students to rethink the very scaffolding through which we write history—and to consider what Cold War history might look like if it began not in Washington or Moscow, but in towns and villages in Vietnam, India, Laos, Thailand, Indonesia, Timor, or Okinawa.

Rather than relying on familiar tropes of “superpower rivalry,” “the long peace,” or “diplomatic theater between global elites,” Cold War Asia poses a more human-scaled question: What did the Cold War mean for ordinary people in Asia? Once we begin listening closely to the answers to that question, we must ask in turn: In what ways, and to what extent, can we still speak of the “Cold War” as a global phenomenon?

References

Gadis, John Lewis. 1997. We Now Know: Rethinking Cold War History. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Ileto, Reynaldo. 2002. “On the Historiography of Southeast Asia and the Philippines: The “Golden Age” of Southeast Asian Studies — Experiences and Reflections.” Workshop for the Academic Frontier Project “Social Change in Asia and the Pacific,” Meiji Gakuin University.

Kwon, Heonik. 2010. The Other Cold War. Columbia University Press.

Masuda, Hajimu, (ed). 2025. Cold War Asia: Unlearning Narratives, Making New Histories. University of North Carolina Press.

────. 2025. “From the Editor: Cold War Asia: Unlearning Narratives, Making New Histories,” Center for Southeast Asian Studies website, available at: https://kyoto.cseas.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/publication/cold-war-asia/

────. 2015. Cold War Crucible: The Korean Conflict and the Postwar World. Harvard University Press.

Suri, Jeremi. 2005. Power and Protest: Global Revolution and the Rise of Détente. Harvard University Press.

Tsuchiya, Kisho. 2019. Workshop Report: Reconceptualizing the Cold War: On-the-ground Experience in Asia 21–22 May and 22–23 June 2019. H-Diplo.

────. 2024. Emplacing East Timor: Regime Change and Knowledge Production, 1860–2010. University of Hawai‘i Press.

Westad, Odd Arne. 2005. The Global Cold War. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「益田肇と冷戦研究:アジアの人々の経験と

グローバルヒストリー」(土屋喜生)