A conversation with:

Shinsuke Tomita, Designated Associate Professor, Nagoya University

Osamu Kozan, Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Satoko Kimura, Associate Professor, Center for Southeast Asian Studies, Kyoto University

Shinsuke Tomita conducts research on land use in mainland Southeast Asia, particularly in northern Laos and Northeast Thailand, from the perspectives of agronomy and ecology.

Osamu Kozan conducts research on the sustainability of large-scale plantations in tropical peatlands in Indonesia from a hydrological perspective.

Satoko Kimura develops methods for quantitative observation of large underwater organisms, mainly small cetaceans (dolphins) to elucidate their ecology and assess environmental impacts on them.

Short Bio:

Kono Yasuyuki obtained his Doctor of Agriculture from the Graduate School of Agriculture, the University of Tokyo, in March 1986. He joined Centre for Southeast Asian Studies (CSEAS), Kyoto University, in July 1987 and will retire in March 2024. During his time at CSEAS, he taught as Associate Professor at the Irrigation Engineering Management Programme, Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) from August 1992 to August 1994 and was CSEAS Director from April 2014 to March 2018. He has been Vice President and Director of the International Strategy Office (ISO), Kyoto University, since April 2018. His majors are Southeast Asian studies and natural resource management. His main research themes include agricultural and rural development path under urbanization and expansion of commercial cropping; Sustainable humanosphere studies to approach global-scale issues from the social, economic and natural perspectives of local communities; and research on local communities and science, technology, and innovation to combine cutting-edge science and technology with local knowledge.

The following is a transcript of a conversation with Professor Kono that took place on October 6, 2023 to commemorate his retirement, reflect on his path, and discuss his vision for the future.

Becoming an Area Studies researcher:

Joining an academic survey in Northeast Thailand as a graduate student

Shinsuke Tomita (hereafter, Tomita): Area studies researchers in the field of natural sciences are rare in the world. Unlike humanities and social science researchers, it has been said that once natural science researchers leave their discipline, they are done with it and cannot return. In the early 1980s, as a graduate student of the Department of Agricultural Engineering, Faculty of Agriculture, the University of Tokyo, you participated in a study conducted by the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University (hereafter CSEAS) of Dong Daeng Village in Northeast Thailand. Living in a village and conducting long-term field research was—and still is—not a common research method in the discipline of Agricultural Engineering. How did you come to participate in the collaborative research and what was the reaction of your home institution at that time?

Yasuyuki Kono (hereafter, Kono): Fieldwork was also done at the Agricultural Engineering Department of the University of Tokyo. When I was a student, I had no idea that I was working on distinctive research, but I was the only one who had conducted long-term field research abroad. At that time, of the twenty Agricultural Engineering students in each grade, about one-third joined the government sector, one-third joined engineering and construction companies, and the remainder moved on to graduate school. The bureaucrats and those who wanted to enter the private sector were all excellent students. Many came from farming families. For example, a friend of mine, the son of a strawberry farmer in Aizu, was seriously thinking about the future of Japanese agriculture. I decided to leave domestic agriculture to them and go overseas.

Tomita: You went to Indonesia and Thailand as a graduate student, but what was the direct impetus for your decision to be an Area Studies researcher abroad? When you started working at CSEAS in 1987, Area Studies was a very small community. Agricultural Engineering was much larger, and you could have returned to that discipline.

Osamu Kozan (hereafter, Kozan): Were you influenced by your friends in the Wandervogel (Mountaineering) Club that you belonged to as an undergraduate?

Kono: I don’t remember making a particular decision to go abroad as an Area Studies researcher. There were 14 members of the Wandervogel Club in the same grade. All of them were serious and secured jobs. I was the only one who became a university teacher. At that time, differently from today, opportunities to go abroad were hard to come by. During my master’s program, I stayed at the site of an irrigation project in Wonogiri, Central Java, Indonesia, under the sponsorship of Nippon Koei Co., Ltd., to study the effects and impacts of water resource development and irrigation system improvement. An interdisciplinary team led by Dr. Hayao Fukui of CSEAS had started a field study in Dong Daeng Village by then. I heard about this when Dr. Yoshihiro Kaida from CSEAS gave an intensive lecture at the University of Tokyo, and after entering the PhD program, I asked to join the team. I stayed in Dong Daeng from August 1983 to January 1984. As rice was cultivated in rain-fed paddy fields, floods and droughts were prominent factors in determining yields. Therefore, I measured the depth of water in the rice fields every day. Based on the data collected in this way, I compiled the results of my research into a dissertation (“A Study on the Agricultural Infrastructure of Rainfed Rice Paddies in Tropical Monsoon Regions,” 1985), in which I evaluated the productivity of rainfed rice cultivation and the potential for improving yields. After that, I was hired as an assistant professor at CSEAS in 1987. At my research unit in the University of Tokyo, I was told that I should first study in Japan before going abroad. I had the option of returning to Agriculture Engineering to advance my career, but regardless of the scale of the research community, rather than working at a domestic university, I still wanted to work abroad. There was a “seller’s market” for graduate students at the time, with plenty of job offers coming in. In retrospect, I think I was a very self-centered, but I was never reprimanded for it.

Promoting interdisciplinary collaborative research:

Exploring the possibilities created by interaction among various disciplines

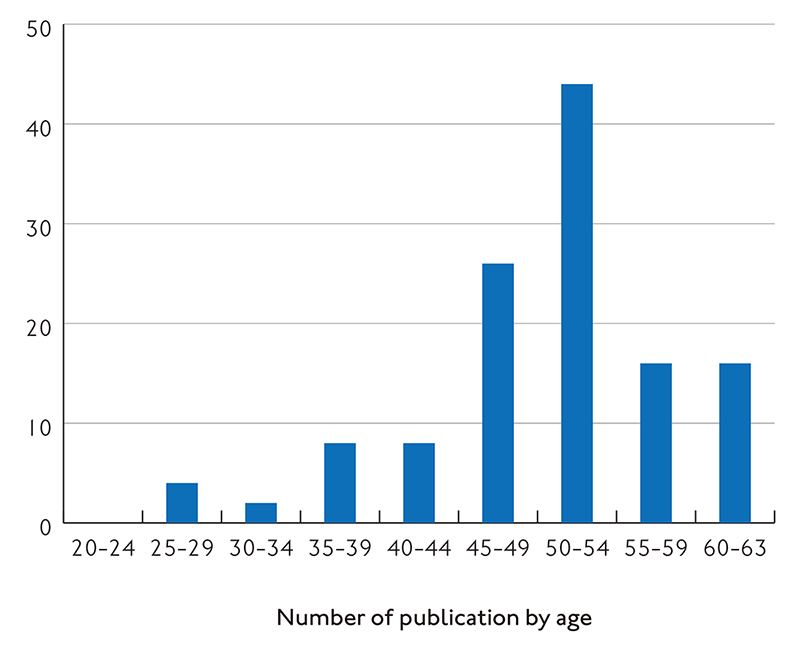

Tomita: Since its beginnings, CSEAS has supported collaboration among natural science, humanities, and social science scholars. This is unique among Area Studies institutes worldwide and is a distinctive feature of CSEAS. According to the KAKENHI (Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research) database,[1] to date you have had 213 collaborators on grant-in-aid projects, an exceptional number by any measure and by far the highest number among CSEAS applicants. You have always engaged with researchers from various disciplines, including in agricultural sciences other than agricultural engineering, natural sciences other than agriculture, and various humanities and social science disciplines. Even within the discipline of agriculture, depending on the specialty, the terms used differs and there are considerable differences in research assumptions. But beyond agriculture, the terms and concepts used are so different that it is almost like a cross-cultural exchange. Communication can be a tough challenge. In addition to KAKENHI projects, you have also conducted collaborative research with the Research Institute for Humanity and Nature (RIHN) (“A Trans-Disciplinary Study on the Regional Eco-History in Tropical Monsoon Asia: 1945–2005” and “Coastal Area-capability Enhancement in Southeast Asia”), the Global COE Program (“In Search of Sustainable Humanosphere in Asia and Africa”), and other projects. What has made you, as an Area Studies researcher, particularly oriented toward collaboration with a highly interdisciplinary approach?

Kono: Your question reminds me of my former graduate students Dr. Tuyen Nghiem and Dr. Yunxi Wu. It is more fun to do collaborative research with people who know things that I don’t know. Also, I can learn by listening to experts in different disciplines. It is not interesting if what we know overlaps. As far as communications problems, if you really try to do collaborative research, you will be able to solve these.

Kozan: Is there more of a barrier to approaching people when you are not familiar with each other’s approach? Even if there is an opportunity to talk at a research meeting or a social occasion, for this to lead to a collaborative project, one must surpass a higher hurdle. You seem to overcome such hurdles and make the necessary preparations for grant applications relatively easily. What triggers you to collaborate with new people? Is it research meetings, reading papers, or some other means?

Kono: It may be that the topics I am interested in require researchers from different disciplines. For example, I had a connection with the Department of Human Ecology, Graduate School of Medicine, the University of Tokyo through Dr. Ryutaro Otsuka. I met him when I attended an international conference at Columbia University. There, I met Dr. Masahiro Umezaki, a member of the same department, and I invited him to CSEAS as a speaker for the Society for Nature and Agriculture in Southeast Asia. Dr. Umezaki and I also went to China and Cambodia together for my KAKENHI project. Dr. Kazuo Watanabe came to CSEAS as a researcher after graduating from Gifu University (United Graduate School of Agricultural Sciences). Of course, some of these relationships continue and some do not. You cannot know whether they will continue or not, or whether they will develop or not, unless you work together.

Tomita: In organizing interdisciplinary collaboration, unless it is promoted with a certain degree of agreement, the research results are uneven. In your projects, what did you emphasize when trying to bring research findings together? Did being a field scientist influence your approach?

Kozan: If we look closely, there are many small results and conclusions from collaborative research. Even when a theme is very broad, such as with the Global COE project, participants discuss common topics, exchange ideas, and find ways to achieve results.

Kono: It is impossible to fit individual studies into a single frame and I don’t think it is necessary to do so. An overarching vision is needed. However, while it is not important to just compile results, it is essential that researchers stimulate each other in the process of collaboration. Stimulation alone will not produce an outcome, but it will have an impact on the next phase of research for each participating researcher. Each participant’s study will have its own findings and conclusions, even if the overall conclusion remains the same as suggested in the project proposal. The Global COE is a prime example. What we said on the project application and what we concluded in the final report were almost the same. However, as everyone was stimulated differently during the process, the results reflect that process in the long run. And I do not see any serious problem with that.

[1] KAKENHI (which is short for kagaku kenkyu hi, or “academic research fund”) is the most dominant academic research grant in Japan.

The diversity of livelihoods, the arc of economic development, and the question of “unique characteristics”

Tomita: In an online public lecture at Kyoto University (“Let Us Think Radically: Southeast Asian Studies – Considering Uncertainty from Rural Southeast Asia”), you said that in order to improve the livelihoods of farmers, it is necessary not only to promote agricultural technology, agricultural production, and other agricultural studies, but also to conduct studies that aim to improve the community. This kind of idea is essentially not found in the agricultural science taught in the Faculty of Agriculture, and I think it is a concept that only an Area Studies researcher who has actually visited the region can come up with. Agricultural scientists may also not acknowledge that people living in rural villages in Southeast Asia have developed livelihoods that do not depend solely on agriculture. Two or three decades ago, many researchers thought that with economic development, rural villages in Southeast Asia would streamline and become more specialized, as in Japan in the past, or that villages would become depopulated, as Japan today. But as we can see today, people are still living in rural villages, and even in Dong Daeng, the diversity of livelihoods has not been lost. Why do you think rural villages in Southeast Asia embrace such diversity, which is different from the trajectory in Japan or other developed countries?

Kono: It can certainly be said that there is a diversity of livelihoods—if we look at the present moment. But although I said that in my online public lecture, I doubt that this trend will continue in the future. In Dong Daeng Village, the number of young people with college or vocational school degrees has increased during the past decade. They have found jobs in government and private enterprises and are now in their 30s. They are not involved in farming and are working full time. With the increase in the number of young people receiving higher education, the situation may change considerably. Therefore, I have my doubts about saying that the development of farming villages in Southeast Asia will differ from that in Japan. But unlike Japan, the quality of governance and administration services, such as the availability of social security and other public programs and the stability of employment, are certainly different in Thailand.

Tomita: Many people predicted that farmers in Northeast Thailand would abandon their traditional livelihoods and shift to other jobs. But if we look at the livelihood changes of the past 40 to 50 years, the shift to full-time employment has been slow. On the other hand, people who have moved to cities invest in their home villages, building irrigation systems, and so on. We do not see this in Japan.

Kono: In Japan, the government is the major entity to improve the land and irrigation facilities.

Tomita: In Japan, many people move to cities, have kids there, and perhaps have their parents join them there as well. In contrast, in Northeast Thailand, many people leave their children with their parents in the village and work in the city. Some return to the village and some do not. What are the factors that contribute to this difference? Is it because the government’s social security system is not yet in place and people must manage on their own? Or are they building a safety net at the family or kinship level?

Kono: That is one of the reasons. In Thailand, many women work, leaving their children with their parents. This is especially true for poor people who move out to cities. The living environment is often not so good in the cities, so they may invest to move to the countryside, for example. Furthermore, land is still attractive as an asset to invest in because land prices are increasing, which is a big part of it.

Tomita: The rice paddies of Northeast Thailand are sandy, the water environment is not good, and the land is in poor condition for agricultural use, but is there anything other than economic reasons why people still invest in them? In Laos, we often hear that people withdraw to coffee farms and orchards when they retire.

Kono: In Thailand, it is common for people who have made money to buy land in the countryside and live on a farm after retirement. This may not have been the case in Japan, but more people may come to enjoy such a lifestyle.

Tomita: One of the goals of Area Studies has been to identify the unique characteristics of areas, but you have said that Southeast Asia has no such characteristic in terms of changes in agriculture and livelihoods.

Kono: It is doubtful that there is one. It used to be assumed that there were unique characteristics of specific areas and in the 1960s and 1970s, it was the primary task of Area and Southeast Asian Studies to clarify them. People did not doubt this. Even today, although this assumption remains in various aspects, it is gradually weakening. It is better to think that if you do research based on the assumption of such a characteristic, you may lose your footing. Various factors, such as globalization, weaken the priority of the question. In the past, farming was done uniquely, using the traditional techniques of each village. Today, however, farmers use machines; they till the soil with a tractor and harvest with a combine harvester. The situation is changing.

Kozan: Can the diversity of Southeast Asia be observed in the present and over the long term? In Indonesia, there is a drastic “boom” every ten years, such as the rapid expansion of oil palm after rubber and coconut palm. Indonesia is more flexible than Japan, and there are many ecological and environmental solutions, not just one.

Kono: Indonesia may be fast-changing, but China is changing faster and more. Southeast Asia is changing piecemeal, and Japan is not changing at all. Still, I am not convinced that this can be called the unique characteristic of Southeast Asia. Let’s continue to try to determine the constraints at any given time and stage, because it is these constraints that cause distinction. If you brand a phenomenon as uniqueness, you will lose your footing.

Designing a society that can adapt to uncertainty:

On the future of Japan as seen from Southeast Asia

Tomita: In your online public lecture “Let Us Think Radically,” you said that it is doubtful that human society will be able to minimize uncertainty in the future and wondered if it would be possible to develop a society that adapts to uncertainty, like the rural societies of Southeast Asia do. One of the arguments of the Global COE program on sustainable humanosphere was that the development pathways in the tropics are different from those in the temperate zone. Does this argument still hold today?

Kono: In Northeast Thailand and in the Global COE program, we emphasized the importance of uncertainty. As for rice cultivation in Northeast Thailand, it is unstable from a long-term perspective of 10 to 30 years. The farmers are aware of this. In this regard, Southeast Asia is different from Japan, at least when we consider spans of 100-200 years. The future is difficult to predict because we have not yet determined what is going to happen and it involves changing trends. We don’t know where we are going and the future remains uncertain.

Tomita: If Japan aims to create a society that can adapt to uncertainty, what conditions are necessary for rural areas currently in decline to play some role?

Kono: Clifford Geertz’s concept of “shared poverty,” the story of Java, is useful. In a densely populated rice-growing area, the labor input for rice cultivation increases to increase rice production to support the ever-growing population. However, as rice production cannot keep up with the increasing labor force, output per capita decreases. This is poverty sharing, and the same is happening in Japan today. Everyone works very hard, but no matter how hard they work, the overall situation gradually trends downward. The same is true for agriculture as a whole and for universities. What should we do? It is very comfortable and satisfying for most people when yesterday, today, and tomorrow are almost the same. As the majority are satisfied, they cannot bring about change. The only way for change to happen is for those who recognize the crisis to destroy the existing regime.

Tomita: Under the current regime, we cannot create a society that can adapt to uncertainty. It may be difficult for the elderly to change, but what about the young? The young [in Japan] are facing a rapid increase in per capita debt.

Kono: Looking at the career prospects of Kyoto University students, fewer and fewer are becoming government officials; most are going to work for large domestic companies. They are trying to immerse themselves in contemporary Japanese society, earn a good salary, work hard in a certain way, and enjoy their lives. Debt is a national story; it is not good if it increases too much, but people feel content.

Kozan: The land and food are safe.

Kono: There are countries where many students want to go abroad whenever they have the chance, such as to attend university or to find a job after graduation, and there are countries where the majority of students are inward-looking and do whatever they can to stay put. Kyoto University has been encouraging students to have more overseas experience while they are still in school, but it has not been successful yet. This is true not only of Kyoto University, but other universities as well.

Kozan: Although today many Southeast Asian students still want to go abroad, the region may become more like Japan in this regard. Indonesia is becoming wealthier. The career paths of the elite may be increasingly restricted to domestic universities and educational institutions. There may be less desire to go abroad than in the past. On the other hand, among the countries I have studied, students in Uzbekistan are still actively trying to go abroad.

Kono: In terms of the desire to work and play an active role in the international arena, Thailand’s has declined, while Vietnam’s is still palpable. When I talked to a professor from a Korean university a few days ago, he said that students no longer want to go abroad at all. It seems that it would certainly be comfortable to live in the country of one’s birth. In reality, however, there are people in countries where this is not the case. Why do people seem to be satisfied to stay in one place when mobility has increased so remarkably around the world?

Tomita: During Japan’s period of rapid economic growth, most people thought that tomorrow would be better than today. It is difficult to see how things will change if the population continues to shrink and the economy is declining.

Kono: If a shared consensus emerges that we must change, change is possible. But that is not happening right now. The government is stable, the young people seem happy, and everyone seems content.

Kozan: Although people [in Japan] complain about many things, they are surprisingly satisfied. If something more tragic happens or the disparity widens to an extreme level, society will finally change.

Kimura: Students [in Japan] don’t go abroad and they seem content with the status quo. Students have told me that they are not particularly interested in houses or cars, all they need is Wi-Fi.

Kono: When people in Dong Daeng Village had children, they moved to new settlements because they thought they would not have enough to eat from the rice fields they owned. Even so, the number of children is decreasing.

Tomita: Is the high level of satisfaction with the status quo related to the declining birth rate?

Kozan: In Indonesia, women are having fewer and fewer children, particularly in cities. With the advancement of technology, rural people are more satisfied with their situation. Before, everyone complained that the peatlands were remote, they wanted to leave as soon as possible, and they did not want their children to use the land. But today, they say peatlands are an excellent place to live, with their oil palm plantations and cell phone towers. Of course, some doubt the monocultural changes in the ecological environment. But it is an attitude that has adapted to globalization and technological evolution. And in the next 20 years, something else may be booming. In this sense, in Thailand and Indonesia there are multiple solutions to stabilize livelihoods compared to cold regions. People survive despite the gap in productivity and between the rich and poor. It is also possible to survive in rural Japan, but the difference is that the natural conditions in Japan are a bit harsher, which tends to make us pessimistic.

Kono: Today Europe is experiencing unprecedented heat waves, floods, and other sudden events, which is fomenting extreme fears. In contrast, Japan has more experience with natural disasters, making Japanese less worried.

Tomita: If the stability of the natural environment is also related to satisfaction with the current situation, is there a possibility that European society will change first?

Kono: Yes. However, the war in Ukraine has led Germany, which aims to decarbonize its electricity system by 2030, to increase coal-fired power generation again. The shift to electric vehicles (EVs) to achieve carbon neutrality is also doubtful at the current pace. It will take a lot of work.

Kozan: Even though Japan is relatively stable in terms of its natural environment, it has been disturbed by monsoons, typhoons, and tropical cyclone-like storms, so it is more resilient than areas that have never experienced such events. The main difference between Southeast Asia and Japan is the attitude after a disaster. In Japan, people demand compensation from the government. In Indonesia, there is not such high expectation. What about in Thailand? Do people think the government should take care of them or not?

Kono: In Thailand, the state has not taken care of the people very well. But since the Thaksin government, the distance between the state and the people has shrunk. Even now, although the state services are limited, people are seeking support from the state. This has increased people’s interest in elections, which has led to political contentions.

Tomita: I see, Japan is stable because people do not expect much from elections.

Kono: People in Japan see no alternative to the way the country is currently governed. The relationship between the government and the governed is so firmly established that it is hard to imagine that there are options. However, even though the future of Japanese society appears bleak, the future of society and the future of individuals cannot be thought of in the same way.

Reflecting on the Dong Daeng Village Survey:

What do the collected data tell us?

Tomita: The long-term survey in Dong Daeng Village accumulated 40 years of data, making it a unique and valuable study. What do you find most interesting about the one-village study of Dong Daeng, why you have resumed your research there, and what are the future prospects of the study?

Kono: I was involved in the project as a graduate student in the 1980s and I have been involved again since 2020. In my future research, I may also reconsider questions around the “unique character” of Southeast Asia. The changes from the 1980s to the 2000s, not only in Northeast Thailand, but also in Southeast Asia, are significant, and we should adequately examine what has changed and how. This is easier to understand if we examine the data where it was collected. It was not until 2002 that there was a plot-by-plot cropping pattern for paddy fields in Dong Daeng Village, and Dr. Shuichi Miyagawa analyzed what this data could tell us. In April 2023, Dr. Isao Hirota of Gifu University organized a seminar on “The Meaning of Surveying the Whole Agricultural Lands” at the Minzoku shizenshi kenkyukai (Ethno-natural History Seminar), coordinated by Dr. Yasuyuki Kosaka, at which Dr. Miyagawa and I reported and Dr. Koji Tanaka commented on our findings. Since Dr. Miyagawa gave a detailed report on the rice cultivation in Dong Daeng Village, I examined the details of the Dong Daeng survey from a broader perspective (“The Whole and the Individual: The Significance of Looking at Everything”). We can see from Dr. Miyagawa’s data that overall paddy rice yields have been gradually increasing, with small annual fluctuations. We need to find out how the instability of rice production relates to people’s lives and livelihoods at the individual household level, and whether a causal relationship is inherent. We can estimate to some extent the livelihood and economic situation of each household unit, the amount of rice production in each household’s rice paddies, and the impact on each household from the 1980s to 2000, with the latter being a snapshot. Dr. Watanabe has started to work on this, but he has not yet been able to analyze it. Although we do not have data on rice production from 2002 to 2020, this may not be necessary, because the number of plots and parcels has decreased due to land readjustment and the plot-to-plot variation of rice yield is not so significant in recent years.

Tomita: Has the number of landowners been decreasing since land readjustment?

Kono: Both the size of the parcels and the number of owners is increasing.

Kozan: Does land ownership have any meaning other than direct economic power, such as proof of being a villager?

Kono: There is an increase in the leasing of farmland, but people do not often give it up. They may not give it up because it is a hassle; it takes a significant amount of time and money to register the land properly.

A versatile team player

Tomita: As the leader of JASTIP, you will be busy after you retire and will have little free time for research. What kind of research would you like to do if you could devote all your time to it?

Kono: In an unrestricted situation, I have never chosen a subject because I want to do this or that research. I chose Dong Daeng because it was my only chance. In 1999, I began a research project in Laos. I was interested in shifting cultivation because that issue highlighted most clearly the conflicting relationship between agriculture and the environment. Later, when many people started this kind of research, I decided to leave this work to Dr. Tomita. I started JASTIP because I thought that appropriate technology was critical. Why was everyone so fixated only on agricultural research? No one was tackling the urgent issue of how to make science and technology more useful in people’s lives in Southeast Asia.

Kozan: What motivates you to take on the task that no one else is doing?

Kono: I would like to leave what others can do to them, or I should leave it to them. When I came to Kyoto University, I was surprised to be asked, “What do you want to do?” I had never been asked such a question at the University of Tokyo, and I thought this was the difference between the institutions. I am not saying that one is better than the other, but when I was asked what I wanted to do….I used to try to think about it, but I decided that I didn’t need to worry about it anymore. It is rare to find someone like me.

Kozan: It seems that you look at the big picture. Whether the world, Japan, or the academic community is moving in a positive direction, you find it exciting and you are happy to contribute, even if it’s not through your own, but rather someone else’s, research. Your altruistic standard is to do your best where there is no one else. Indeed, you have changed your role depending on the person(s) you were working with, like a versatile soccer player. If you were working with someone aggressive, you would follow them; if you were working with someone quiet, you would pull them along; which was more common, or which was more fun?

Kono: In Northeast Thailand, I did some following and some pulling. It is easier to follow someone, but both are fun. I am indebted to CSEAS, so when everyone said I should be the director, I had to do it. That’s the way it is.

The Center’s role in society:

To those who will be responsible for future studies

Kono: As I said at the 50th anniversary of the Center, the question of “what are the unique characteristics of Southeast Asia,” which used to be the biggest question in Southeast Asian studies, is no longer helpful. We need to create the next question. I think it is how knowledge of Southeast Asian society can contribute to the future of the world. We should not continue to do the same kind of Area Studies that we have done in the past. Instead, we should remove as many restrictions as possible from our research activities and consider and discuss how we can promote the research necessary for today’s society. The most proactive thing I did during my tenure as the director of CSEAS was to integrate CSEAS with CIAS (the Center for Integrated Area Studies). We should always consider what we can do to remain relevant. With a budget of billions of yen and significant human resources, we do not need to “advocate” for Area Studies, it will naturally grow if the results of such research are constantly shaped and produced.

Kozan: Indeed, the idea of an institute is to be renewed every 20 years or so. I feel that the ball is in my hands, that it is time for me to run and that I need to get a little taller. As for the ongoing industry-academia collaboration program with Daikin Industries, we have been talking about what we can do and how we can cultivate the various potentials of CSEAS.

The importance of life-work balance

Kozan: When my third child was born, I had to carry her on my back to every class and meeting. One day Dr. Kono said to me, “Because we study people, you should be fully engaged in your family even though it may be hard sometimes, Kozan-kun.” I was grateful that both my superiors at that time, Dr. Kono and Dr. Mizuno, both had an understanding of child-rearing. These little words from Dr. Kono have stayed with me, and I think they came out naturally as a very human response, rather than being chosen in a planned way.

Kono: I say what I feel in the moment. It is important to talk with people. It is better to comment than not to comment.

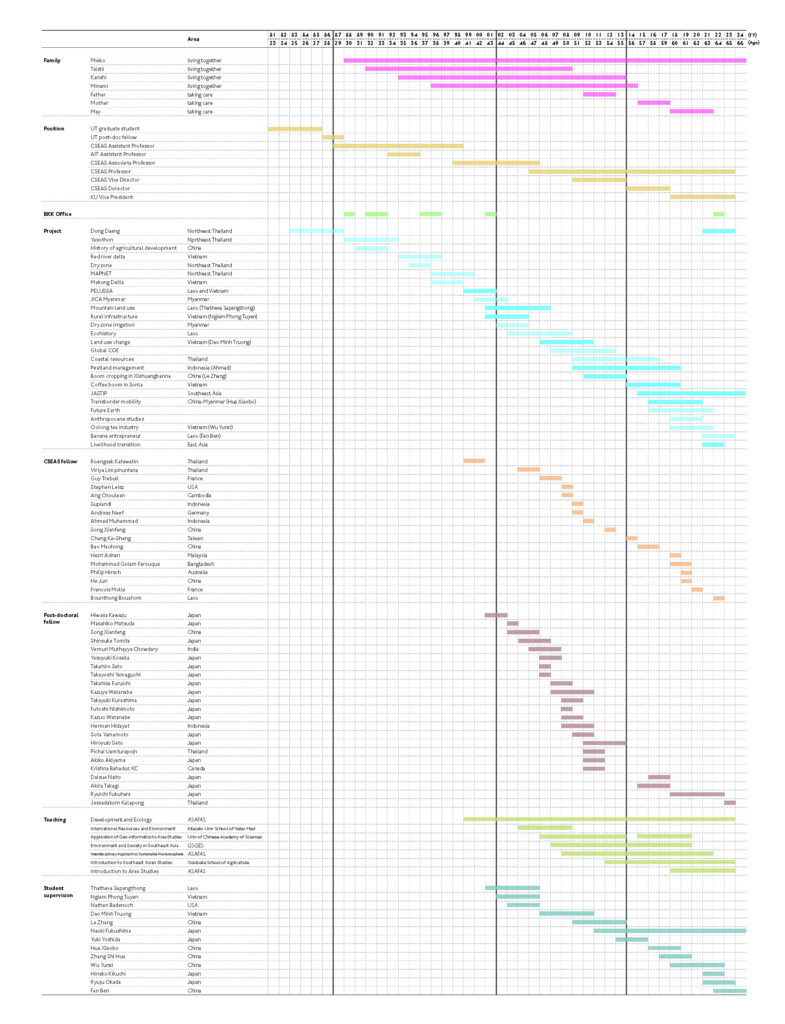

Kimura: Can you describe the three milestones in your career timeline that you provided as a reference?

Kono: The first milestone was joining CSEAS. The second turning point was when my older children were in the upper grades of elementary school and I stopped taking long fieldwork trips overseas. In the 1980s and 90s, I used to frequently conduct fieldwork for 2 or 3 months at a time, but once they reached that age, the longest trip I took was for about two weeks. When my children were small, I sometimes took them with me on my fieldwork, but I started to realize that such long trips were not very good for them. The third point, 2014, was the year I became the director of CSEAS, and after that, long-term fieldwork became even more difficult. Traveling for two weeks while serving as director and avoiding official duties is almost impossible. The timeline is therefore divided according to the length of the fieldwork period, or rather, the broad phases in my research.

Kimura: This is indeed a fascinating chronology, and one that I would like to emulate. Dr. Kono, thank you so much for sharing your story with us today.

Reflecting on the journey of research

Timeline

Gallery

Field survey in China, 1990–92

Mainland Southeast Asia

Various surveys of GCOE program

Maritime Southeast Asia

Cambodia

With students and former students

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「研究のフロンティアを探し求めて:人と自然と社会の共生」

河野泰之教授退職記念インタビュー