Satoru Kobayashi (Area Studies, Anthropology)

My first visit to Kyoto was for a school excursion (to Kyoto and Nara) in the spring of my third year of middle school. The purpose of the trip was to learn about traditional Japanese culture. We were given handbooks on temples and shrines and taught the history of the two ancient capitals during the period when they flourished. At the time, I was more fascinated by the beauty of the temples, shrines, and statues than their history. Although I don’t remember much about the trip, I must have enjoyed it.

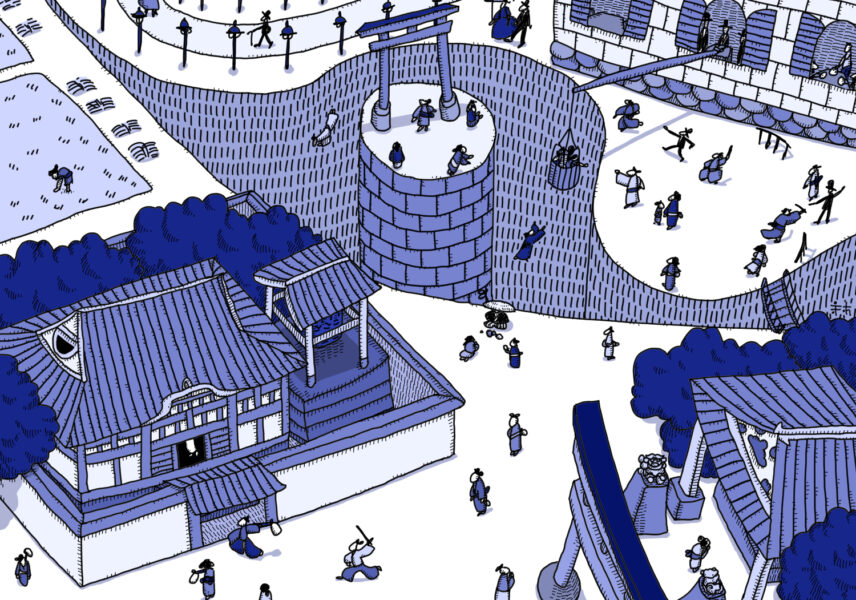

Kyoto is said to be a city steeped in historical heritage. But how did the people who lived in its streets, and created its buildings and statues, survive? What changes have there been in more recent years? In what ways did Buddhism, which was the source of the power to create such forms, support people in their lives? The school’s learning materials categorized the streets, temples, and Buddhist statues of Kyoto as historical heritage, using phrases such as “cultural assets representative of the Tenpyo culture of the Nara period.” One read, “Kyoto is a city where historical heritage lives and breathes.” No information was provided to help answer the above questions.

Two books have since made me consider these questions in concrete form. The first is Yoshio Yasumaru’s Kamigami no Meiji ishin: Shinbutsu bunri to Haibutsu kishaku 神々の明治維新─神仏分離と廃仏毀釈 (The Meiji Restoration of the Gods: The Separation of Shinto and Buddhist Religions and the Abolition of Buddhism, in Japanese) . From it, we learn that before the Meiji government built temples and shrines across Japan, a landscape vastly different from the present one existed. Whether in the capital or the provinces, Japan originally had a religious culture that worshipped deities without distinction between Buddhism, Shintoism, and the rest. However, the Meiji government, which aimed to abolish the traditional political system and build a modern state, chose Shinto as the religion to support the nation, and only certain gods were designated as important. This led to fierce conflicts among factions across the country who supported the traditional system and those who supported the new one installed by the Meiji government.

The second is Yoshihiko Amino’s Mu-en, kugai, raku: Chusei Nihon no jiyu to heiwa 無縁・公界・楽─日本中世の自由と平和 (Mu-en, Kugai, and Raku: Medieval Japanese Constructions of Peace and Liberty, in Japanese), which attempts to find a form of human liberty in medieval Japan that is different than that upon which Western modernity relies. Through this book, I learned the concept of “Mu-en” in Japanese and “asyl,” which has a Greek origin and exists in multiple Western languages. As places of religious order, temples and shrines have the power to sever various relationships in this world. Although it is difficult to find traces of this power in the temples and shrines that we see today when we walk the streets of Kyoto, this book allows us to imagine the religious culture of Japan at a time when logic and power differed from that of the secular world. This imagination extends beyond Japan. Could it be that Southeast Asian societies also had a kind of liberty that differed from that of the West?

(Illustration by Atelier Epocha)

This article is also available in Japanese. >>

「京都を歩き、想像を拡げる」(小林 知)